Most of the attention given to the dreadnoughts focuses on those of the major powers, Britain, the US, Germany, and Japan, with lesser attention on those of France, Italy, and Russia. But this is not the full story of the big-gun warship. Several smaller nations also bought them before World War I. The most prominent of these ships are those involved in the South American Dreadnought Race.

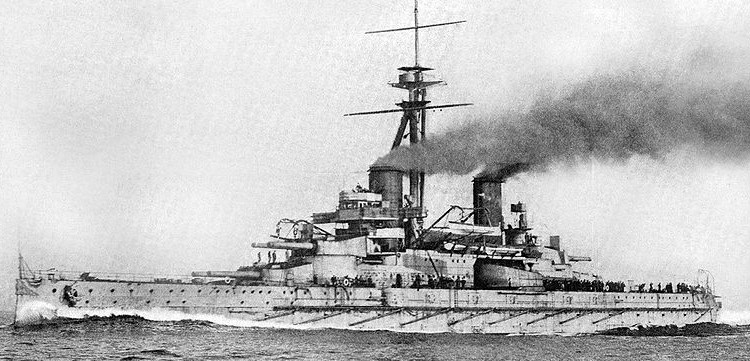

Minas Geraes in 1910, shortly after delivery

In 1907, flush with cash from a boom in rubber and coffee, and attempting to assert itself as a world power, Brazil ordered a pair of ships from British yards. These ships, the Minas Geraes class, were briefly the most powerful battleships in the world. Each ship had 12 12" guns, and a 10-gun broadside thanks to the unusual combination of wing and superfiring turrets. In response, Argentina and Chile both rushed to order dreadnoughts of their own.

Minas Geraes firing a broadside

These ships never fought a naval battle, instead playing colorful roles in Brazil’s internal politics. A flogging on Minas Geraes only months after her completion triggered the Revolt of the Lash, a naval mutiny brought on by the harsh physical punishments common in the Brazilian navy. Soon, other elements of the fleet, including her sister ship, Sao Paulo, joined the mutiny. The mutineers managed to win their cause, convincing the government to abolish corporal punishment and improve living conditions for the sailors.1 This led to the ammunition and gun breeches being stored ashore, and the resulting collapse of the Brazilian naval threat went a long way to damp the enthusiasm for battleships in neighboring countries, although it was too late to cancel their orders.

The mutineers aboard Sao Paulo

When Brazil joined the First World War in 1917, the ships were offered for service with the British Grand Fleet, but were turned down. They had not been modernized since completion in 1910, and advances in technology, particularly fire control, meant that they were unsuitable for front-line service. The British superiority in battleships, particularly with the recent addition of the 6th Battle Squadron from the USN, probably played a part, too.

In 1922, Sao Paulo suppressed the Copacabana Fort revolt by a group of Brazilian Army officers against the existing elites. However, her crew mutinied in 1924, apparently seeking the release of the prisoners of that same revolt. They tried to entice Minas Geraes to join them, and when that failed, they steamed for Uruguay, which granted the rebels asylum and returned the ship to Brazil.

Minas Geraes after her refit

Minas Geraes was reconstructed in the 30s, most notably being converted for oil firing. Sao Paulo was not, as she was in such poor condition that it was deemed uneconomical. Sao Paulo did serve as the flagship of the Blockade of Santos2 during the 1932 Constitutionalist Revolution. Neither ship played a role in the Second World War due to age and obsolescence, and both were sold for scrap in the 50s. Sao Paulo came adrift while under tow in the Atlantic, and was never seen again.

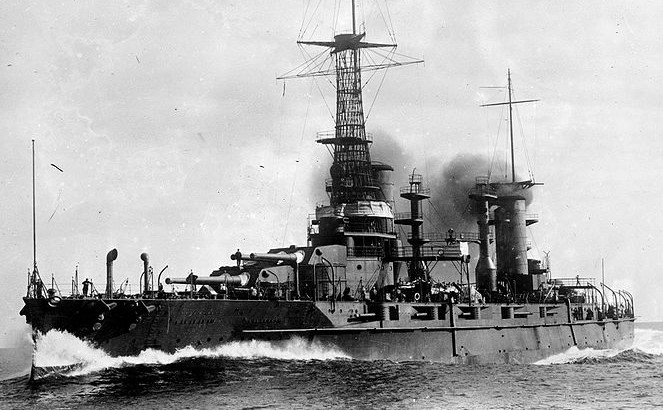

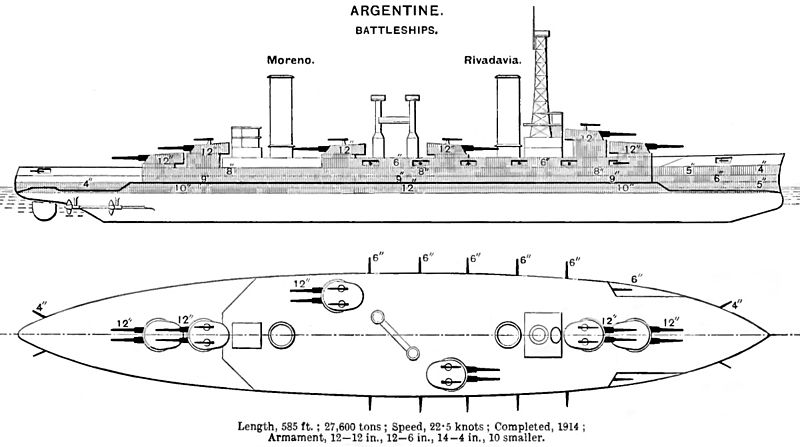

Rivadavia shortly after delivery

Argentina and Chile had responded to the Brazilian purchase by buying dreadnoughts of their own. Argentina bought a pair of ships, Rivadavia and Moreno, from the US. This was a shock, as the Latin American governments traditionally bought their arms from European suppliers.3 A US government loan, various diplomatic assurances and a promise to include the latest fire-control equipment secured the contract. Each ship was armed with 12 12" guns in twin turrets. Four were on the centerline, while the last two were in offset wing turrets, theoretically allowing a 12-gun broadside. Like all such arrangements, it didn't work particularly well.4

The ships became the objects of considerable diplomatic maneuvering even before World War One. The dreadnought race was cooling with falling commodity prices and the Revolt of the Lash, and Argentina looked at putting the ships up for sale. The US government objected, as it did not want its latest fire control equipment5 falling into other hands. The contracts for the ships did give the US first right of refusal, but the USN did not want the ships, as they were of a design the USN considered obsolete6 and they likely would have replaced new construction in the budget. When the First World War began, the situation became even more tangled. Germany and Britain were both concerned that the ships would fall into the hands of their enemy, and both accused Argentina of plotting with the other to turn the ships over, probably by way of a third party in the Balkans. The US, wanting to stay neutral, pressured Argentina to keep the ships, which they eventually did.

Moreno in 1946

These ships had a much less colorful history than did their Brazilian counterparts, dividing their time between reserve, training duty, and serving as transport for diplomatic missions. Both survived into the late 50s before being scrapped. Moreno's 96-day tow to Japan was then a world record.

Almirante Latorre as HMS Canada

Chile bought two battleships from the British, Almirante Latorre7 and Almirante Cochrane, each armed with 10 14” guns. However, at the beginning of WWI, these ships were purchased by the British, with Chilean concurrence.8 Almirante Latorre was commissioned as HMS Canada in 1915, while Almirante Cochrane was converted to the carrier HMS Eagle, and commissioned in 1918. Canada participated in the Battle of Jutland, where she fired 42 rounds from her main guns, taking no hits. She was sold back to Chile in 1920, and regained her original name. Eagle remained in British service until sunk by a U-boat in the Mediterranean while covering a convoy to Malta.

Back in Chilean service, Almirante Latorre was the scene of a mutiny in 1931, brought on by the massive effects on Chile of the Great Depression.9 Facing massive pay cuts and serious inflation, the sailors mutinied and took their officers prisoner, and the mutiny spread to other elements of the armed forces. Eventually, an attack by the army and bombing from the air force induced the mutineers to surrender with their demands unmet.

Almirante Latorre in the 30s

Almirante Latorre was inactive during the most of the 30s, and although she was thoroughly obsolete by the start of WW2, the US approached Chile about purchasing her after Pearl Harbor. She was placed in reserve in 1951, and sold for scrap in 1959.

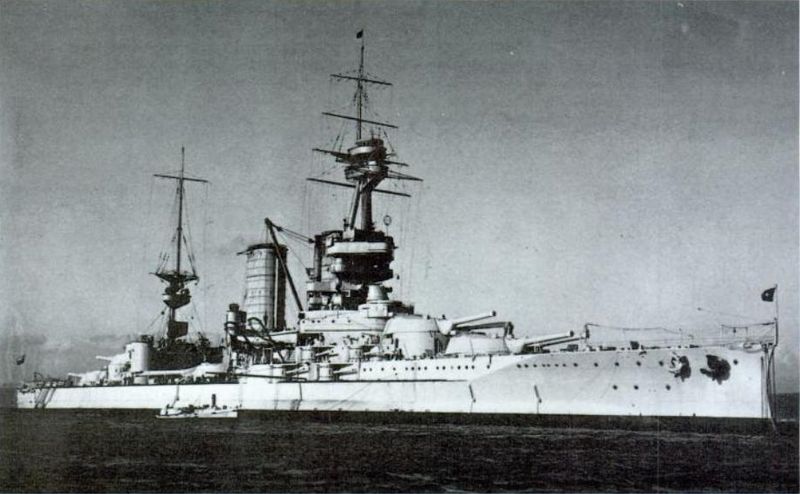

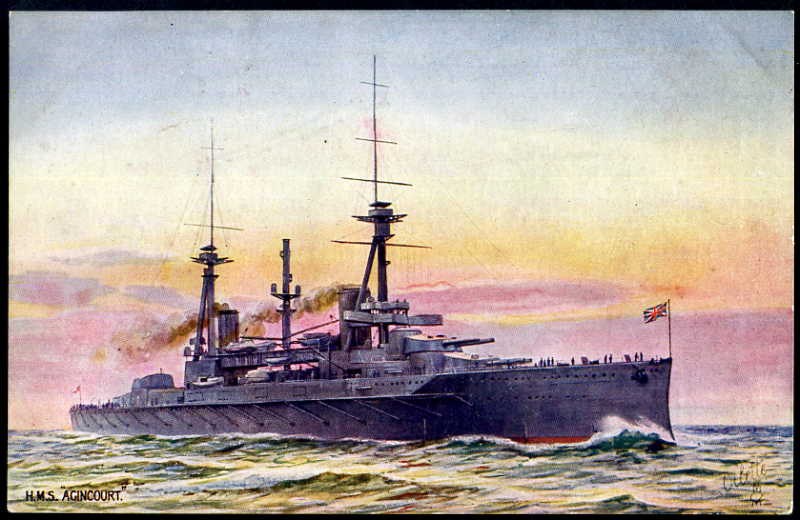

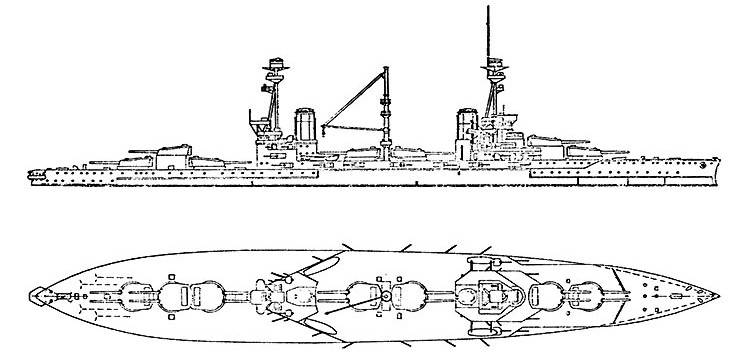

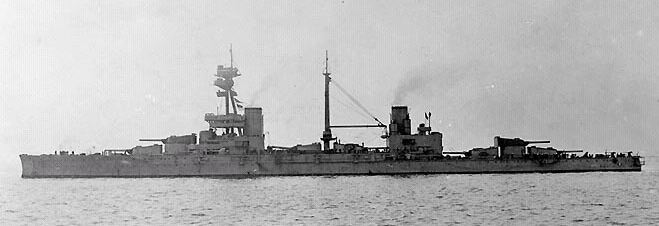

There is one other very interesting ship that deserves to be mentioned in the context of the South American Dreadnought Race, although she never served under a South American flag. The ship in question had the distinction of being owned by three different governments within 12 months, and of carrying the most heavy guns ever mounted on a dreadnought. She began life as Rio de Janeiro, a follow-on to the Minas Geraes. Originally, she was to have had 13.5" guns, but a change in government prompted the Brazilians to gain superiority with number of guns instead of size in hopes of benefiting from logistical commonality. As a result, she mounted 7 twin 12” turrets on the centerline.

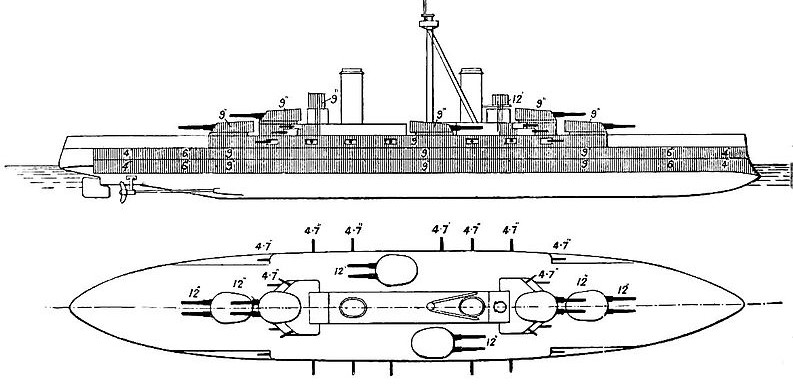

A drawing from 1914, when the ship was known as Sultan Osman I

A slowdown in the Brazilian economy in 1913 prompted them to put the ship up for sale, and the Ottoman Empire swooped in to buy the ship to accompany the other battleship they had on order, the Reşadiye. Renamed Sultân Osmân-ı Evvel, the former Rio de Janeiro was completed in August of 1914, just in time to be seized by the British, who were afraid (correctly) that the Ottomas would turn her over to the Germans. She entered RN service as HMS Agincourt four days later. The takeover caused considerable anti-British feeling in the Ottoman Empire, as the ship had been purchased by a public subscription campaign.

Agincourt shortly after entering service

In British service, she was a definite oddball. Manned by a combination of the crew of the Royal Yacht and men released from the detention barracks,10 she was considered the most comfortable vessel in the fleet, giving her the nickname of 'gin palace'.11 She was widely considered a handsome ship, and a full broadside was said to resemble a battlecruiser blowing up. The normal British nomenclature for naming turrets broke down, and the captain simply named the turrets after the days of the week, although they were numbered 1 to 7 on official plans.

At Jutland, she was part of the 6th Division of the 1st Battle Squadron, a unit where each ship was from a different class and had different guns. During the battle she fired 144 12” shells, and is believed to have made at least 3 hits on German ships, without taking damage herself.

Agincourt later in her career. Note the removal of the boat deck over the central two turrets.

After the war, the British attempted to sell Agincourt back to Brazil. Unfortunately, this fell through, as did a plan to convert her into a depot ship, and she was sold for scrap under the Washington Naval Treaty.

1 An interesting side note is that the mutineers handled the ships very well, contradicting the belief that the Brazilian Navy was incapable of operating the ships effectively even before the mutiny. ⇑

2 Ironically, Santos is the main port of Sao Paulo city. ⇑

3 In fact, these were the only dreadnoughts built in the US for a foreign country. ⇑

4 It's also notable as the only example of wing turrets on an American-built battleship. ⇑

5 This was one of the major selling points of the ships, and apparently nobody asked what would happen if the ships were sold to another power. ⇑

6 By this point, the US had moved on to the All-or-Nothing designs pioneered by Nevada. ⇑

8 Chile was an important source of nitrates for making explosives, and the British didn't want to risk angering them. ⇑

9 The League of Nations declared Chile the hardest-hit of any country. ⇑

10 Crewing battleship on short notice is not easy. ⇑

11 From the phrase "a gin court". Oscar Parkes, who served aboard, said that a knowledge of Portugese was required to work some of the fittings. The fact that she was comfortable for the enlisted men is somewhat notable for a ship built by a minor power, which are notorious for luxurious officer's accommodations and subpar enlisted quarters. It's possible that Brazilian memories of the Revolt of the Lash played a part in this. ⇑

Comments

Interesting contradiction. Today I'd just assume the US government was so arrogant as to believe its technology was two full generations ahead of everyone else. It's harder to believe that was the case a hundred years ago, when the Royal Navy still dominated the high seas (and sold modern dreadnoughts to anyone with cash), but not out of the question. But I still wonder whether there might have been some other agenda behind blocking the sale. Any idea who the customer might have been?

I just realized that I left out one crucial fact there which nicely resolves the contradiction, and have added a footnote to that effect. Rivadavia was a pre-Nevada design, and the USN by this point was buying Standard Types. So in terms of design, she was obsolete. The contract specified that the ships would get the latest USN fire control, though, and it was presumably easier to get Argentina to take them than it was to pay to get it off. I'm a little bit surprised that they didn't write in that the fire control equipment was nontransferable, but I guess it wasn't.

Apparently, someone in the Balkans friendly to one of the belligerents after the war broke out. Before that, the US was worried about its equipment ending up in the hands of Germany or Japan. If I had to pick a likely candidate before the war, it would be Greece or the Ottomans.

While looking up stuff on this, though, I found some interesting details on the response to the Revolt of the Lash that made a lot more sense of why the other powers were so eager to sell.

How much do you know about the Dardanelles action? I remember reading about it in Manchester's Churchill bio years ago, Manchester being adamant that the British could have successfully forced the strait if they hadn't lost their nerve. Wiki has a paragraph supporting this and another paragraph hedging. I do notice that this view is much more favorable for Churchill, turning Gallipoli into a good strategic idea bungled by subordinates.

(I would guess that general histories' treatment of military topics makes military history buffs facepalm a lot)

Not as much as I'd like to, and not enough to say for certain if the naval attack could have been made to work. I recall it being widely believed that going in early (like, after Goeben) would have been easy. Not sure about 1915.

This, I will agree with. Using your mobility to attack a foe's flanks is the classic strategy of a sea power. The fact that the British messed up the implementation at Gallipoli doesn't mean that it was a bad idea, and when you look closely, it really didn't harm Churchill's career. He was scapegoated briefly, then came back when the uproar died down.

I love how the first sentence of this article is becoming a check-list.

It was always more or less intended to be that way.