In honor of our recent discussion of the early battlecruisers, I’m reposting the story of possibly the most influential capital ship of the First World War. The battlecruiser Goeben and the light cruiser Breslau formed the German Mediterranean Division, stationed at Pola, the main Austrian naval base. They had been sent in 1912, to project German power into the region, with the wartime mission of disrupting the flow of troops from French North Africa (modern Algeria) to France. Two years later, they would play a major role in the opening days of the First World War.

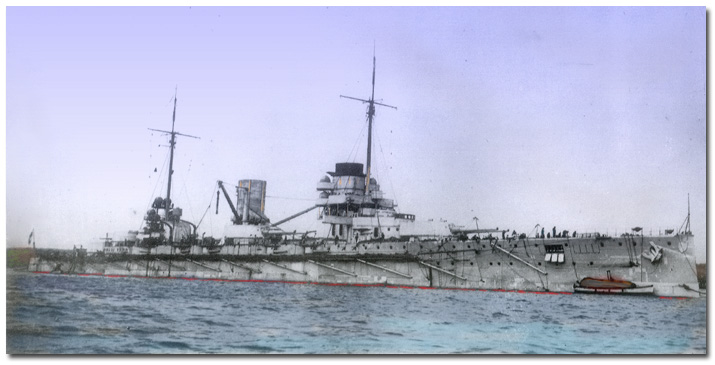

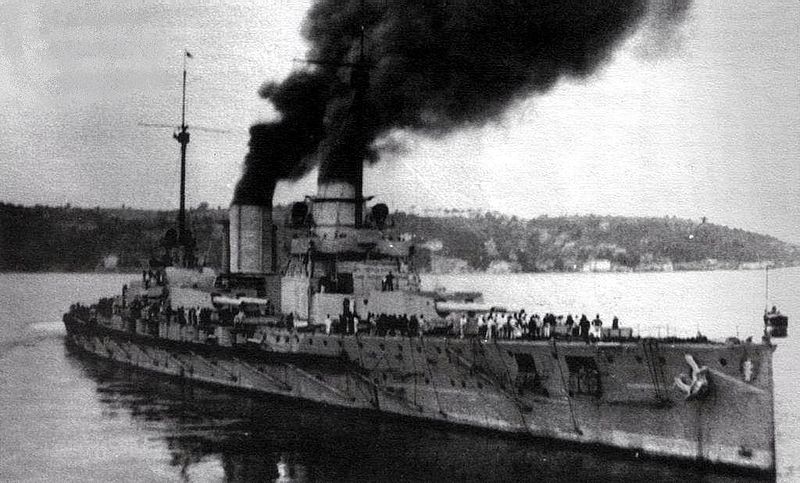

SMS Goeben

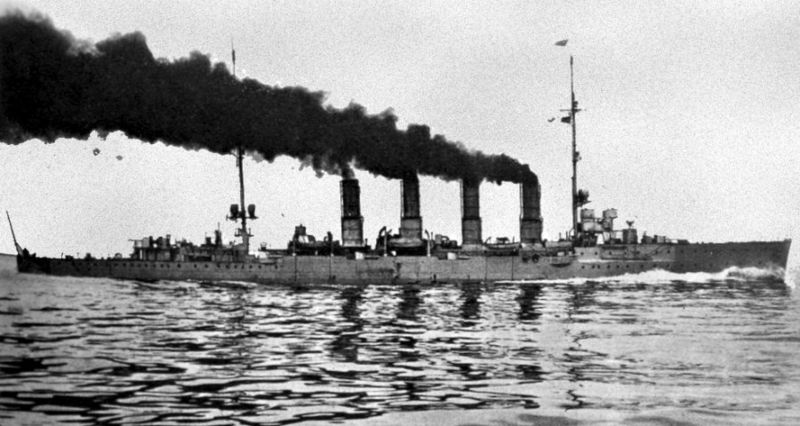

The British Mediterranean fleet, composed of the battlecruisers Inflexible, Indefatigable and Invincible, four armored and four light cruisers and a flotilla of destroyers, was ordered on July 30th 1914 to cover the French transports, and on August 2nd, to shadow Goeben while maintaining a watch on the Adriatic in case of a sortie by the Austrians. Admiral Souchon, in command of the German force, had already sortied, but was spotted in Taranto, Italy, by the British consul, who reported the findings to London. The Admiralty ordered Indomitable and Indefatigable sent to Gibraltar to guard against a sortie into the Atlantic, presumably an attempt to return to Germany. Souchon, however, was headed for Bone and Philippeville, embarkation ports for French troops in Algeria. On the evening of the 3rd, after having slipped through the Straits of Messina ahead of British searchers, he was informed that the Germans had signed an alliance with Turkey, and he was to head for Constantinople immediately. He ignored these orders, and bombarded the ports (doing very little damage) at dawn on August 4th before heading back to Italy to coal again. Shortly thereafter, Indomitable and Indefatigable sighted Goeben, but the British had not yet entered the war, and they did not engage. Admiral Milne, the British commander, reported the contact, but did not tell the Admiralty (headed by Winston Churchill) that the Germans were heading east, and Churchill continued to believe they would attempt to interfere with the French troop movements.

Both Goeben and the British ships were having boiler problems, reducing Goeben’s speed from 27 to 24 kts, although this was still faster than the British ships could manage. The light cruiser Dublin managed to stay with the Germans for a while, until she lost them in a fog. By the next morning, the Germans were safe in the neutral port of Messina, and the British had declared war after the invasion of Belgium. Because of the need to stay well outside Italian territorial waters, Milne was forced to cover both sides of the strait. Inflexible and Indefatigable were placed on the north side of the strait, while the light cruiser Gloucester was sent to cover the south, due to the continued British misunderstanding of the German plan. Indomitable was sent to coal at Bizerte, Tunisia, instead of at Malta, another unfortunate choice.

British ships pursuing Goeben and Breslau

The Germans had problems, too. The Italian authorities were slow to supply coal, and Souchon had to take coal from German merchant ships in the port. However, he wasn’t able to get enough to allow him to reach Constantinople before the Italians ordered him out of the port entirely on the evening of the 6th. The Ottomans had decided not to join the war yet, and the Austrians (not yet at war with France and unsure of their fleet) were unwilling to help Souchon, making his situation worse. For some reason, Souchon was allowed to decide where to go, and he chose Constantinople, hoping to force the hand of the Turkish government.

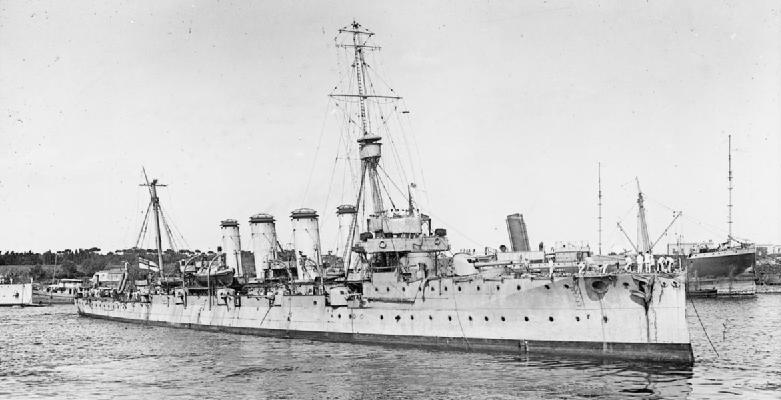

SMS Breslau

Milne assumed that Souchon would go either west for the Atlantic, or head into the Adriatic, which was already patrolled by a squadron under Admiral Troubridge, composed of the armored cruisers Defence, Black Prince, Warrior, and Duke of Edinburgh, escorted by 8 destroyers. Goeben would have had a massive advantage in a gunnery duel, leading Troubridge to plan a night attack in the entrance to the Adriatic where superior numbers would tell. However, he was under specific orders not to engage a superior force, which had been intended to mean the Austrian fleet.

HMS Gloucester

When Souchon left Messina, he was shadowed by Gloucester.1 The cruiser reported that the Germans appeared to be headed for the Aegean instead of the Adriatic. Troubridge headed south, hoping to intercept Souchon at dawn, where he could close and use his destroyers to launch a torpedo attack. Unfortunately, only three of his eight destroyers had sufficient coal to keep up on his dash south, and at around 4 AM on the 7th, it had become obvious that he would not reach the intercept in time. He thus applied his orders about not engaging a superior force, and turned back.

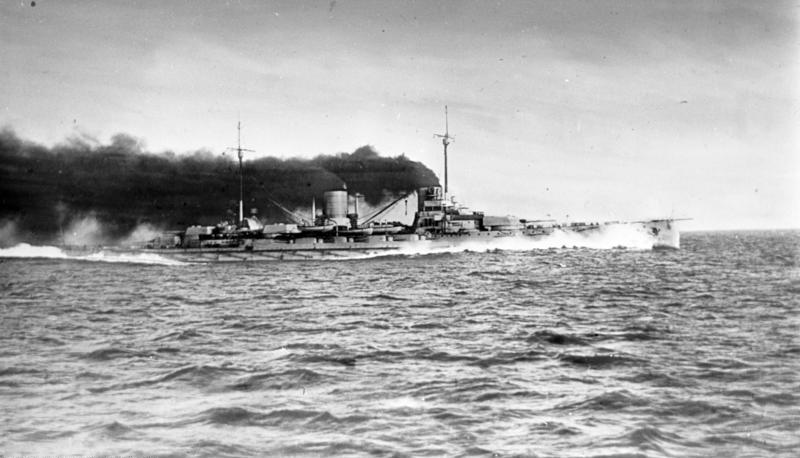

Goeben at speed

Souchon didn’t know he was now safe, and that the battlecruisers were far to the west. He continued to strain towards a rendezvous he had set up with a collier off of Greece. Gloucester briefly engaged Breslau, but neither side inflicted serious damage, even when Goeben fired at long range. Finally, on the afternoon of the 7th, Gloucester, her coal nearly exhausted, broke off at Cape Matapan as the German ships entered the Aegean.

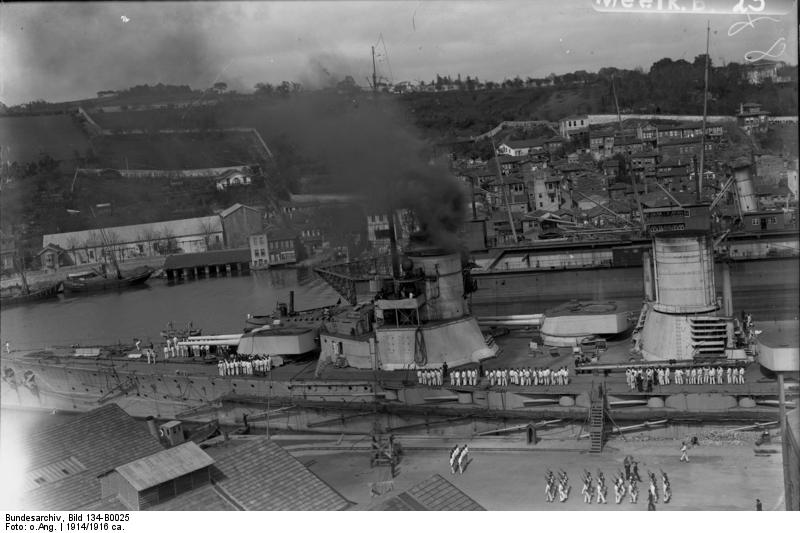

Goeben in 1915

Souchon met his collier on the 9th, while the British were distracted by miscommunications about the situation with Austria. It wasn’t until midnight on the 8th that Milne took the battlecruisers west, and he still thought it was all an elaborate feint, and took station off the entrance to the Aegean until the early hours of the 10th, when Souchon, alerted by the increase in radio traffic, set off again at dawn after coaling for 24 hours.2

By the time he reached the entrance to the Dardanelles, columns of smoke from the British were visible on the horizon. Souchon, uncertain of how the Turks would respond, requested a pilot, and the Turks decided to allow him through. The British were denied entrance, and the pursuit was over. To avoid the legal complications inherent in then-neutral Turkey allowing the ships to pass into the Black Sea, they were officially transferred to the Turkish Navy on August 16th, and renamed Yavuz Sultan Selim and Midilli respectively, although they retained their German crews. Souchon was made commander-in-chief of the Ottoman Navy.

Goeben in the Bosporus

The gift of the two ships did much to swing Turkish public opinion in favor of the Central Powers, particularly after the British seized two ships building for Turkey and paid for by public subscription. On October 29th, Souchon, under the guise of taking his ships to sea, and with the concurrence of some Turkish officials, raided the Russian coast. Goeben3 bombarded Sebastopol, while Breslau shelled the grain port of Novorossiysk. Damage was fairly minimal, but it did force the Ottomans into the war a few days later.

Burning oil tanks following Breslau’s bombardment

There was a short battle off Cape Sarych on November 18th, where Goeben engaged five Russian pre-dreadnoughts. The results were inconclusive, and Goeben took a hit which killed 13 men and damaged one of her secondary guns, while doing light damage to one of the Russian ships. Goeben struck two mines on December 26th, which was only partially repaired during the war, due to the absence of drydocks that would fit her. She bombarded Allied positions at Gallipoli, which brought her into brief contact with Allied battleships. May 10th saw another inconclusive encounter between Goeben and the Russian fleet, while the new Russian dreadnought Imperatritsa Ekaterina Velikaya engaged the ship on January 8th, 1916 with no results on either side. A coal shortage limited operations in 1917, until the armistice with the Russians late in the year.

On January 20th, 1918, Goeben and Breslau sortied again, this time into the Aegean. They sunk a pair of British monitors4, and were preparing to attack the base of the pre-dreadnought covering force when they ran into a minefield. Breslau sank, while Goeben took three hits. She was beached just outside the Dardanelles, and crippled for the rest of the war.

Yavuz with Missouri in 1947

Goeben was originally to have been transferred as a prize to the RN, but the Turks held onto her. She was in bad shape, but a new floating dock was purchased, and she was finally repaired in 1930. She remained in service until 1950, undergoing further refits. The Turks offered to sell her to the West German government in 1963, but the Germans declined, probably because of her poor material condition. She was towed to the breakers in 1973, the last dreadnought outside of the United States.5

Recent Comments