In 1907, Teddy Roosevelt ordered the bulk of the American battlefleet sent from its bases on the Atlantic to the West Coast in a test of its readiness to deploy quickly, in the event of a war with Japan. The resulting force, known as the "Great White Fleet" due to the gleaming paint scheme used, reached San Francisco in May 1908, to a tremendous welcome.

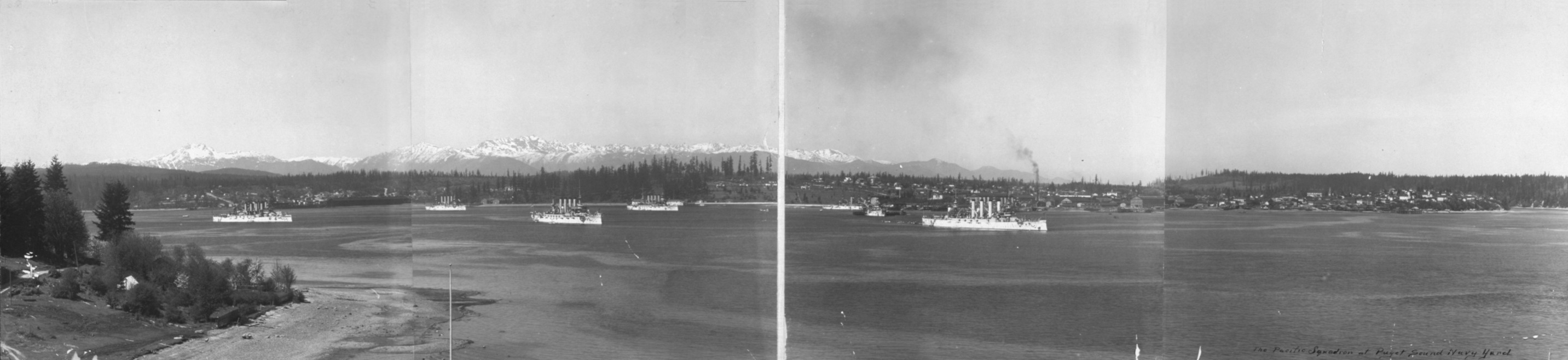

The Great White Fleet in San Francisco Bay

Even as the fleet was completing the last legs to the West Coast, it was announced that it would return to the East Coast via Australia, the Philippines, and Suez. This promptly set off a diplomatic storm, as nations along the route vied to get a visit from the fleet. Australia had moved first, issuing an informal invitation before the battleships had even passed through the Strait of Magellan, but American efforts to forestall further invitations by announcing the route early proved futile. New Zealand and Japan were quickly added to the itinerary, although in both cases only one port would be visited. The Chinese invitation was also accepted, although only after considerable wrangling over the site of the visit and the number of ships to participate. A British invitation for a visit to the UK was turned down due to time constraints, but their offer of their numerous bases along the route, most prominently Gibraltar, was gratefully accepted.

The fleet in Puget Sound

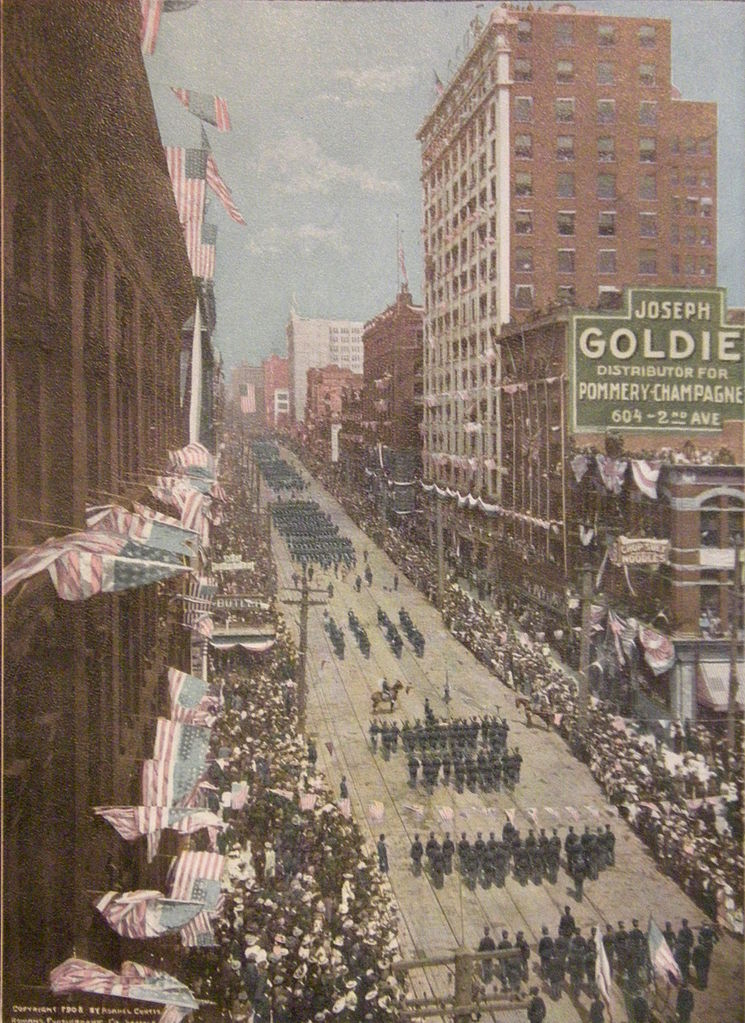

But before it set out towards the Pacific, the fleet was going to visit more of the West Coast. After 12 days in San Francisco, the fleet departed for Puget Sound, steaming along the coast so that the cities they passed could get a glimpse of the fleet. 400,000 people welcomed the fleet to Seattle in much the same way that it had been greeted at every previous stop. Then it was time for the fleet to disperse to the West Coast navy yards, so that the ships could be drydocked before beginning the long voyage home. Each ship carried a new passenger, a bear cub presented to act as the ship's mascot. These joined the growing menagerie on decks, which included at least one tiger.

The parade for the fleet in Seattle

The fleet that had steamed out was slightly different from the one that arrived in San Francisco. The battleships Maine and Alabama were detached due to engineering problems. Maine was notorious for excessive coal consumption, while Alabama had a cracked cylinder head. They were replaced by Nebraska and Wisconsin, already on the West Coast, and returned via a more direct circumnavigation, arriving back home in October, four months ahead of the rest of the fleet.

Pineapples piled on the deck during the fleet's visit to Hawaii

But despite all this, the fleet sailed on July 7th, under the command of Admiral Sperry. Only 129 men, less than 1% of the fleet's personnel, deserted despite the 5 months remaining in the cruise. As the ships steamed towards Honolulu, Sperry immediately set a more energetic pace than Admiral Evans, the previous commander, had. He was also willing and able to go ashore and take part in festivities. The Hawaiian visit was somewhat handicapped by limited port facilities, but it had long-lasting effects on the islands. While Hawaii had been American territory for some time, it had not been the subject of much attention. The arrival of the fleet brought it into the national eye, and newspaper reports of its six-day visit made much of the climate and the islanders. The fleet also steamed past the leper colony on Molokai, a salute that would be echoed by Missouri on her round-the-world voyage in 1986.

The fleet steaming past Pago Pago en route to Auckland

The leg of the journey from Honolulu to Auckland was the longest continuous run of the entire trip, and despite the improvements in engineering performance the older ships were very close to running out of coal when they arrived in New Zealand.

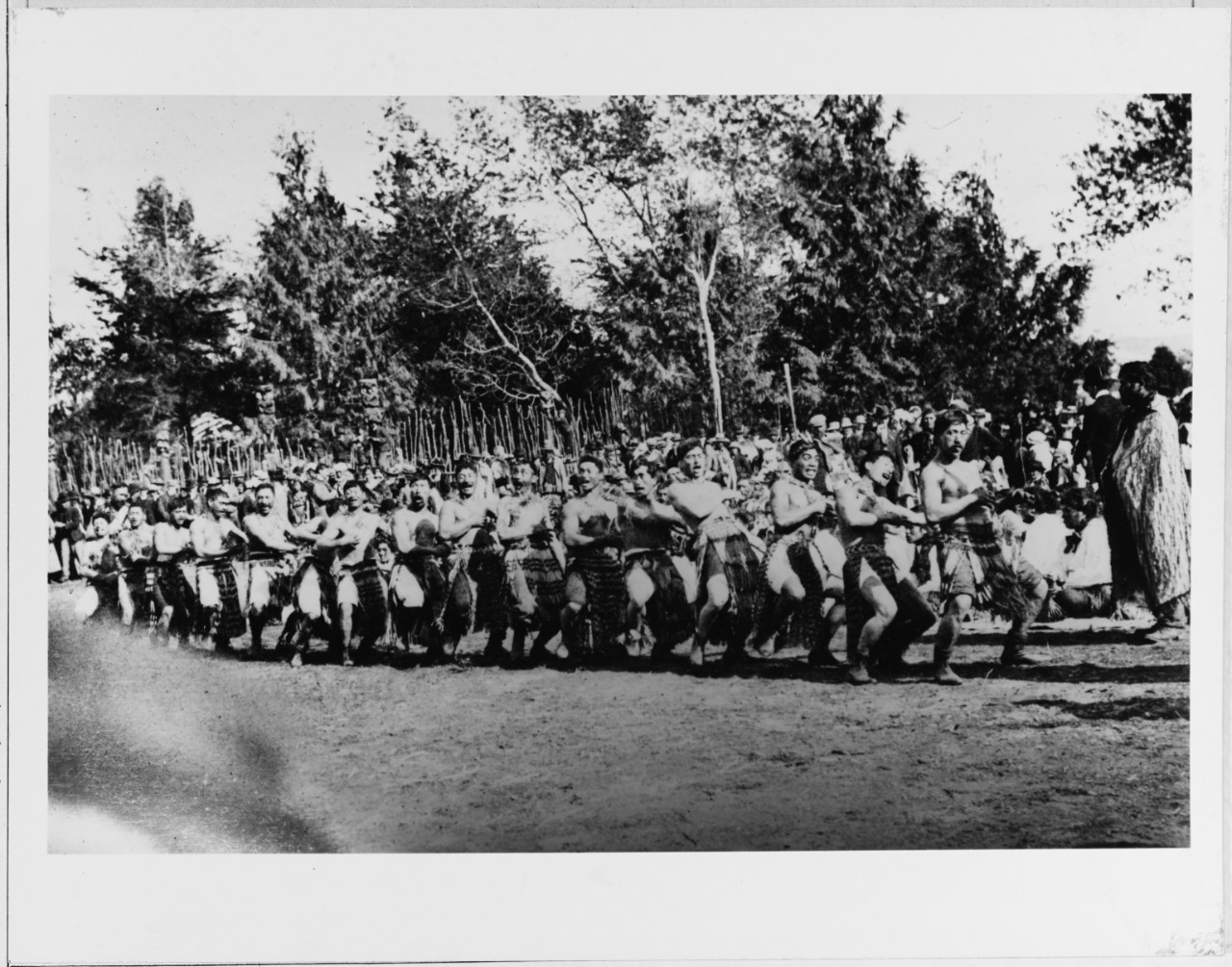

Maoris perform a Haka for Admiral Sperry

The New Zealand they arrived in greeted them with even more enthusiasm than was normal on the voyage, due to the looming Japanese menace. In the aftermath of the Russo-Japanese War and the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, which led to the withdrawal of the vast majority of British naval power in the Pacific, Australia and New Zealand felt vulnerable. Concerns about Japanese immigration compounded tensions, and made them look across the Pacific to the United States as a counterbalance to the threat. A crowd of 100,000, 10% of the country's population, lined the shores as the fleet pulled into Auckland. Parades and parties marked the week the ships remained in harbor, and the sailors sent well over 40,000 postcards home.

The fleet conducting a searchlight illumination in Sydney

The next stop was Sydney, where the crowds were even larger. Though the exact number is not known, it was generally agreed that more people turned out to greet the Americans than had shown up for the celebration of the founding of the Commonwealth. The plan to parade the American Naval Brigade was placed in peril due to Imperial regulations that prohibited the landing of armed men in Australia. Eventually, a compromise was reached, allowing the men to parade with arms but without ammunition. The only blotches on the visit were outrage when Admiral Sperry saluted the Archbishop of Sydney, angering the local Anglicans, and when the Coal Lumpers Union refused to coal the hospital ship Relief because non-union bluejackets had coaled the battleships. Fortunately, the furor died down and enough sailors were on hand to allow Relief to get underway.

The men of the fleet on parade in Melbourne

Melbourne gave its best welcome, although by this point the men of the fleet had become rather jaded, and barely noticed the cheering crowds and boats of spectators buzzing around. It took at least an hour and a half for the men to reach the city from the ships, but the visit was well worth it for most men. The pre-planned activities suffered from extremely low attendance. One dinner laid on for 3,000 men had exactly one show up on time, rising to seven over the next two hours. This was in many ways a measure of the success of the visit, which was acclaimed by the men as the best port call of the voyage. It was reportedly rare to see a girl who had managed to get a sailor all to herself, with most bluejackets seen in public having one on each arm. Not surprisingly, an epidemic of men overstaying their liberties broke out. Even though the battleship Kansas stayed behind for five days to retrieve stragglers, as well as picking up mail and conducting an investigation into a collision between an American collier and an Australian steamer, over 100 men were left behind in Melbourne, as opposed to only 15 in Sydney, and fewer in other ports the fleet called at.

Coaling in Albany

The last stop in Australia was in Albany, a small town where the fleet was to take on coal. Coal had become a serious issue by this point, as three of the six colliers scheduled to meet the fleet in Auckland had failed to arrive on time, leaving them short 16,000 tons and forcing them to procure extra coal in Australia. Sydney and Melbourne had been told that no local coal would be needed, and a scramble ensued to source as much as possible. About 13,000 tons were finally delivered to the fleet, allowing it to make Albany. Unfortunately, only three of the six colliers intended for that stop made it before the fleet, and plans were made for a coaling stop in the southern Philippines. Two of the tardy ships arrived four days after the battleships, allowing them to proceed direct to Manila, although Missouri and Connecticut had to stay a few hours after the rest of the fleet sailed to finish coaling.

Next time, I'll pick up the story with the arrival of the fleet in the Philippines, their destination in the event of war with Japan, and their return home via the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean.

Comments

"The battleships Maine and Alabama were detached due to engineering problems. Maine was notorious for excessive coal consumption, while Alabama had a cracked cylinder head. ... and returned via a more direct circumnavigation, arriving back home in October, four months ahead of the rest of the fleet."

So they had serious mechanical problems and decided that the best way to go back to their home port was circumnavigating the world?

What was a normal desertion rate back then?

@doctorpat

They're on the west coast, well away from their home bases. Options are either to go back around South America or to just complete the circumnavigation. The former is annoying, and requires you to arrange coal and so on. The latter lets you use a string of bases. They did San Francisco-Hawaii-Guam-Manila-Singapore-Ceylon-Aden-Suez-Naples-Gibraltar-Azores-Home. Which is about twice as many stops as the fleet made during its cruise. I'd guess Alabama ran one shaft, and Maine just coaled a lot.

@redRover

I don't have precise figures (or the relevant book to hand) but I believe that the fleet lost 100-150 men in San Francisco and <10 in most other ports. This was low for the era, as morale in the fleet was apparently pretty good.