By 1898, Spain's empire in the Americas, once the largest in the world, was a husk of its former self. Revolutions early in the century had seen the Spanish colonies from Chile to Mexico become independent nations, leaving only Cuba and Puerto Rico under the Spanish flag. In the Pacific, they retained the Philippines, Guam, and a scattering of small islands.1 But even these remnants rested uneasily. Cuba had first revolted against Spanish rule 30 years earlier, and another effort to win independence had broken out in 1895, followed by a similar revolutionary war in the Philippines a year later. The US watched all of this with growing interest. American businesses essentially controlled the Cuban economy, and Cuban revolutionaries staged a very successful propaganda campaign to convince the US to intervene, aided by harsh measures the Spanish used to fight the Cuban guerillas and the famous "Yellow Journalism" of American newspapers. However, President McKinley wanted to end the conflict peacefully, and offered to serve as an intermediary.

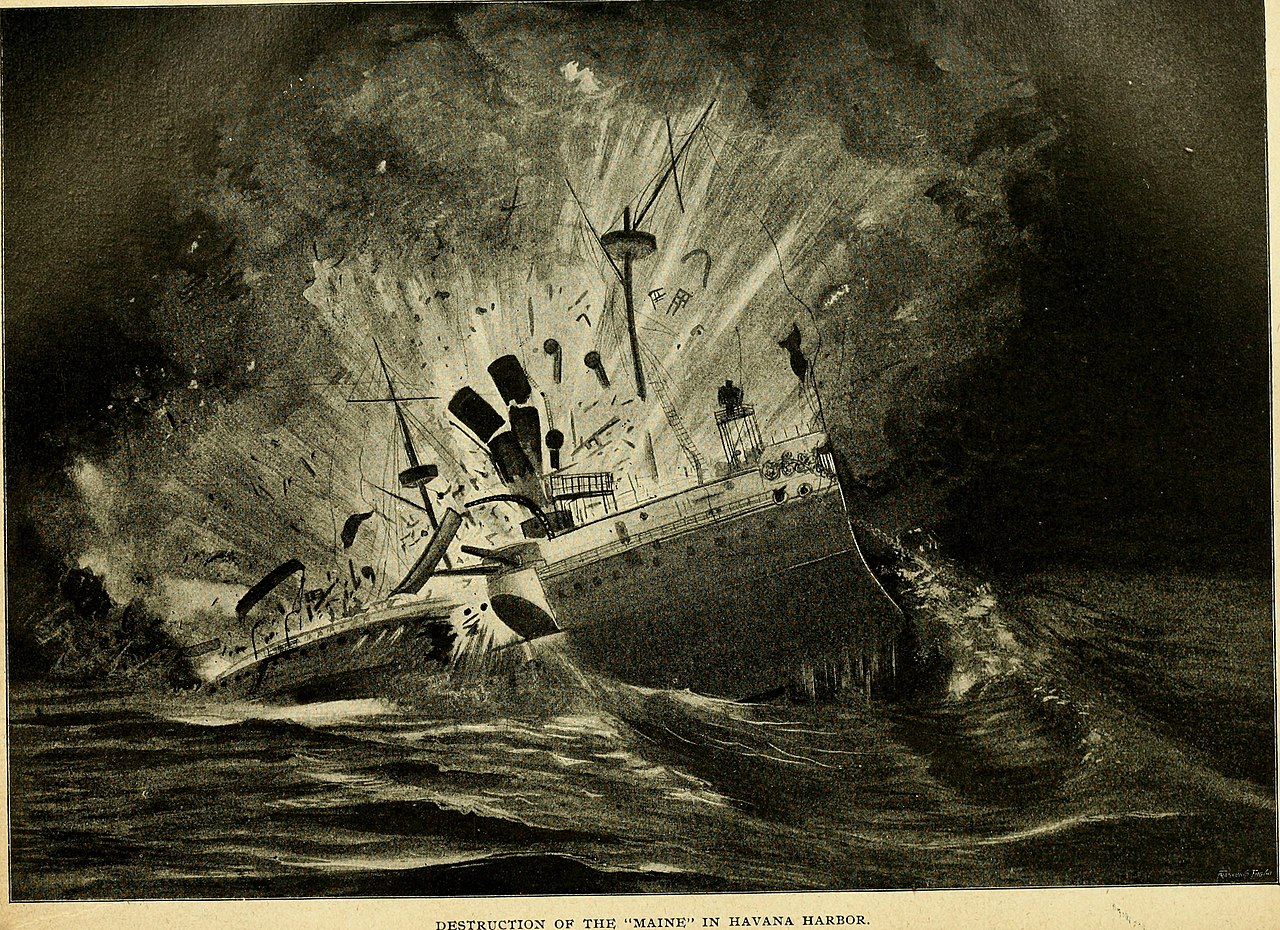

USS Maine in Havana Harbor

Into this cauldron was sent the American battleship Maine. The first battleship built for the US Navy, she was by this point obsolescent, with staggered turrets and no protection from QF guns. However, this would not seriously hinder her mission of protecting American citizens and interests in Havana, which depended much more on her status as a US warship than on her combat power. She entered the harbor on January 25th, 1898, and while the Spanish were not particularly friendly, they didn't interfere with the crew. Her Captain, Charles Sigsbee, was not ignorant of the danger that the Spanish would take some action against the ship. In fact, some locals had called for vengeance against the "Yankees" for sending a man-of-war to their waters, and demonstrated against the ship. Sigsbee ordered extra sentries posted, and kept a quarter of the watch on deck near their battle stations. He also made sure that any visitors were carefully monitored for "infernal machines", and that steam was kept up to allow the turrets to operate in an emergency. Unfortunately, his crew was unable to sweep the harbor for mines, or to use Maine's searchlights, which would have been interpreted by the authorities as a hostile gesture.

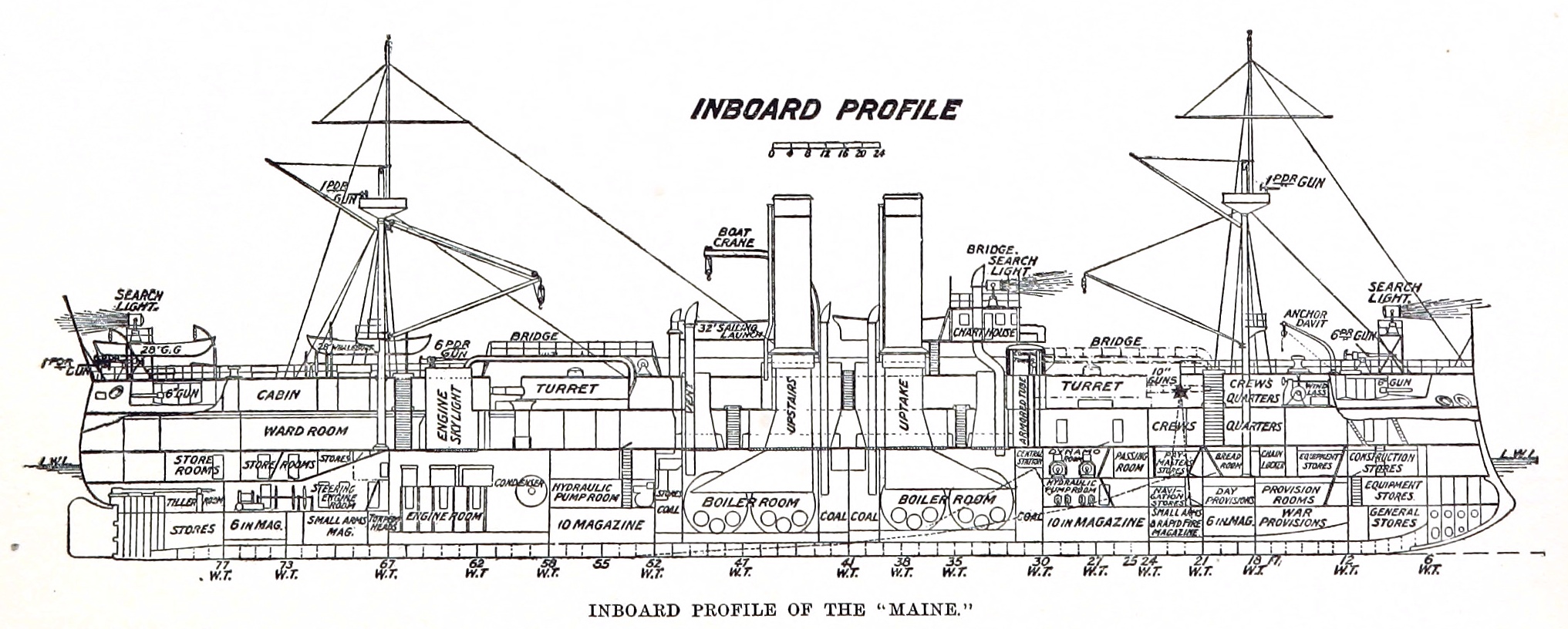

Despite these precautions, tragedy struck at 9:40 PM on February 15th, three weeks after Maine's arrival in Havana. Outside observers heard a small explosion, like a gunshot, and then her forward magazine, containing over 5 tons of powder for the 10" and 6" guns, detonated, demolishing the forward third of the ship. The men in the aft section reacted quickly, flooding the after magazine and trying to fight the fire, but it was soon apparent that Maine was doomed. The boats were launched and what wounded could be evacuated were. Other vessels in the harbor and the Spanish officials ashore contributed their boats to the rescue efforts. Captain Sigsbee, in accordance with naval tradition, was the last to leave the ship. Of the 355 men aboard, 253 were either killed in the explosion or drowned immediately thereafter, while another 8 died of their injuries later. 24 of the 26 officers survived, as their quarters were in the after section of the ship, while the sailors and Marines were berthed forward.

The wreckage of Maine

The following morning, the surviving officers inspected the wreck. The aft half of the ship was largely intact, with the mainmast2 still standing. Forward of this, the superstructure and deck had been blown up and folded back, while towards the bow, the bottom of the ship had been twisted so that a section around Frame 17 protruded above the surface.

As soon as he was ashore, Captain Sigsbee telegraphed the Navy Department with news of the disaster, ending with a request that "public opinion should be suspended until further report". This was obviously impossible, and the papers of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer quickly began urging war. The US Navy quickly put together a court of inquiry, which concluded that the explosion was caused by a naval mine on the outside of the ship. This intensified the calls for war, and in April Congress officially declared war. "Remember the Maine - To Hell with Spain" quickly became the rallying cry.

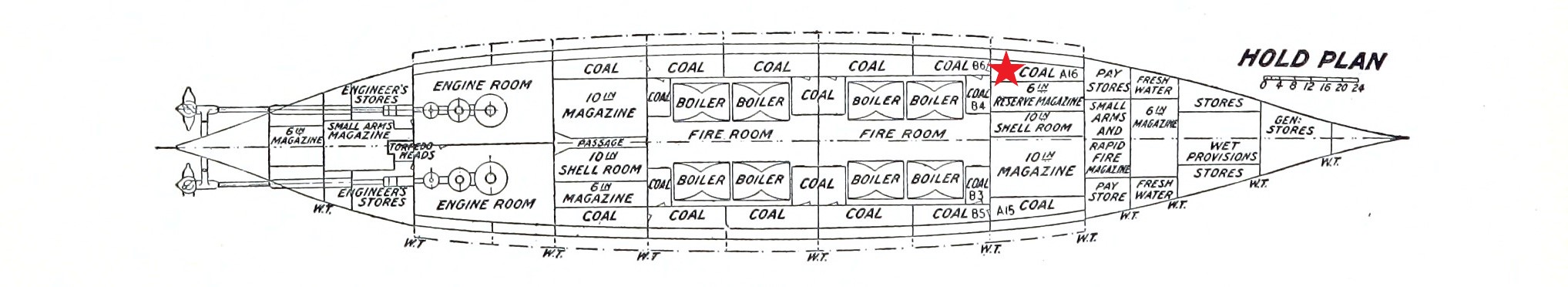

But did Spain actually destroy the Maine? The answer remains at least somewhat controversial to this day. The initial US Navy inquiry, chaired by William Sampson, later famous for his victory at Santiago, concluded that a mine was responsible for the explosion, on the basis that most witnesses reported two explosions and that some sections of the hull near the explosion were bent inward, which would be expected from a mine. The other main hypothesis, that a coal bunker fire3 caused the explosion, was supported by a Spanish inquiry at the same time, which pointed out that there was no direct physical evidence of a mine. The harbor had been calm the night of the explosion, which made the use of a contact mine unlikely as there was no current to carry it into the ship, and no trace of wires for a remotely-detonated mine were found.4

The wreckage of Maine inside the cofferdam

The US got a second chance to investigate in 1911. It was decided that the Corps of Engineers should build a cofferdam around the wreckage, allowing a more through investigation of the incident as well as providing a means of recovering the bodies. The Cuban authorities also wanted the wreckage of Maine removed from the harbor, and the after half was made watertight, taken out to sea, and scuttled. The court of inquiry, which included several naval constructors who took meticulous accounts of what they found, concluded that a mine had indeed been responsible for setting off the magazines, although they believed it to have been somewhat smaller and in a different location than the Sampson board.

A plan of Maine's hold, with red star designating the location of the hypothetical bunker fire.

There the matter rested until the mid-70s, when Admiral Hyman Rickover, father of the Nuclear Navy, commissioned another investigation, which concluded that a spontaneous fire in the coal bunker had set off the powder in the 6" reserve magazine, which then detonated the 10" and main 6" magazines. The most recent investigation was carried out on behalf of National Geographic in 1998,5 and it concluded that while a coal bunker fire could indeed have caused the explosion, and might even have done so swiftly enough that the crew would not have noticed, there was damage to the bottom of the ship that was more likely to result from a mine than from an internal explosion alone.

We will probably never know definitively what happened that night in Havana Harbor. The best physical evidence available seems to support the theory that a mine was responsible, but the motive of any such miner remains uncertain. The Spanish government did not want a war, but certain nationalist elements apparently did. Or it could have been a false flag operation carried out by Cuban rebels hoping to bring the US in on their side. Due to the lack of overwhelming physical evidence, the mine must have been quite small, and whoever planted the device would have presumably been only trying to damage the Maine.6 It is also worth pointing out that no evidence of any plot to mine the Maine has come to light. As a result, it seems more likely that the explosion was a result of a coal bunker fire,7 although neither theory can be ruled out.

But whatever the truth of the matter, the result was inevitable. Despite the best efforts of President McKinley and the business community, popular demand for war led, on April 21st, to a blockade of Cuba, followed by a declaration of war on the 25th. Even before that, both sides had begun to prepare for war, which is where we'll pick up the story next time.

1 There were also Spanish possessions in Africa, but they played no part in the Spanish-American War, so I will ignore them here. ⇑

2 In a ship with two masts, the forward one is called the foremast, while the after one is the mainmast. ⇑

3 This is a fairly common problem with coal, which tends to spontaneously heat itself if stored improperly. There had been fires on other ships at the time, notably Texas and Cincinnati, and the US board rejected the theory on the grounds that they didn't believe it could have happened without someone noticing. ⇑

4 Another option would be a towed mine, which could have been brought into contact with Maine that evening without leaving a trace. ⇑

5 The article can be found in the February 1998 issue of the magazine. The entire archive stretching back to 1888 can be found online by subscribers, and there's a lot of great stuff there. I spend far more time with the digital back issues than I do with the new magazines. A more detailed description can be found in the April 1998 issue of Naval History magazine, which is free online to Naval Institute members. ⇑

6 Unless the device was physically planted on the ship itself, the perpetrator would have been unable to place it precisely enough to have a good chance of a magazine detonation, and the technology of the day would have made it exceedingly difficult to send a diver in with a charge without being detected by the ship. ⇑

7 I'd give about 70% odds on the coal bunker. ⇑

Comments

"She entered the harbor on January 25th, 1918"

"The US got a second chance to investigate in 1911."

One of those dates is wrong.

I'm off by 20 years. No clue why I typed 1918 instead of 1898.

Do you know if any of the investigators considered the possibility of torpedoes? An unlikely hypothesis, but I'm somehow in the mood to consider conspiracy theories today, and it seems that anyone who might have benefited from a Spanish-American war could have arranged one by slipping one of those newfangled Whitehead gizmos over the side of a merchant ship in the harbor.

I believe they did. The big problem is that torpedoes of the day left a trail of bubbles, and the crew should have seen that. My best source only discusses a torpedo from shore, but I don't have a good enough map of Havana Harbor to figure out if this is because a merchant ship couldn't have gotten the right angle or what.

The explosion was almost three hours past the end of nautical twilight, and from your description Maine wasn't allowed to use searchlights. It seems like a bubble trail might have gone unnoticed in that environment.

I think the question of motive and capability inform the answer of the means. As far as I can tell, there would be almost no reason for the Spanish to attack the Maine, and that view seems to have been recognized at the time as well. Leaving out the far-fetched yet somehow popular idea the US did it, that basically leaves Cuban partisans on both sides. I doubt these groups would be able to procure any sort of high-tech weapon like a whitehead torpedo, or really even a good mine.

OK, so did the Hearst syndicate have a branch office in Fiume, and were there any suspicious expense reports in late 1897? No, wait, that was the plot of a James Bond movie...

We could also add Germany, which actually acquired some of Spain's colonial territories after the war, to the list of suspects. Or any of a number of powers that might have expected Spain to eke out a win and so constrain the growth of American power. False flag attacks are never a likely hypothesis, because of the severe consequences if they are revealed, but they only remain implausible if people keep checking to be sure.

One would think it would be fairly straightforward to tell whether an explosion happened inside the ship or outside it. In one case the plates would buckle outward; in the other, inward. Is there some complicating factor?

@Johan: You must have skimmed this part: "Outside observers heard a small explosion, like a gunshot, and then her forward magazine, containing over 5 tons of powder for the 10″ and 6″ guns, detonated, demolishing the forward third of the ship."

The debate is about the 'small explosion', which had to have been near the magazine. I'd call a nearby magazine explosion one heck of a 'complicating factor', myself!

After all, the vast majority of all of the damage would have been done by the magazine, not by whatever set it off.

This could go either way, and I don’t have enough information to tell. I think the trail was pretty substantial, and sometimes, you get marine phosphorescence with that kind of stuff. Also, there’s the fact that hitting the magazine was a very lucky shot indeed, and the plotting would have been on the basis of a damaged but still very much alive warship looking for what happened, and without a giant explosion to destroy all the physical evidence. Also, the location of the hit on the bottom suggests very strongly that it wasn’t a torpedo. Torpedoes almost always leave a very distinctive water column, which was totally absent in this case.

I don’t really buy a false flag either. Germany couldn’t have known they’d pick up the Spanish colonies (they were offered to the US first, but we refused to pay for them, so Germany bought them) and every other candidate is even less likely.

@Johan

Pretty much what David said. The magazine explosion did a number on the ship, and there’s debate over the remaining physical evidence. A few plates are bent in in a manner suggestive of an external explosion, but there are those who have made a case that they could have been bent that way by inrushing water after the magazine explosion. I’m not really qualified to judge, but based on what I read/saw, I’d say that from the physical evidence of the ship alone, external charge is more likely. Once I shift this prior to account for means and motive, coal bunker starts looking a lot better.

The other problem with the torpedo theory is that the torpedoes of the day were all contact fused, and would have left fairly obvious signs of a strike on the side of the ship. The evidence of an exterior explosion all came from underneath the ship.

While doing a bit of research about the Whitehead torpedo, I learned about the Battle of Drøbak Sound. It can't be said that it wasn't a capable weapon, as 40-year old Whitehead torpedoes were used to sink a WWII cruiser.

Drobak Sound is a rather interesting battle, and a lesson in why "obsolete" weapons can still be dangerous if you get close enough to them. I'd like to write about the Norwegian Campaign eventually, and I recently got a book on it, but I've had other demands on my time.

Assuming Spain really did want to start a war, how does attacking the Maine compare to other possible ways to provoke the US? (and is the situation different if we only talk about 'nationalist elements')

If there was an obviously better way to get the US to declare war on you, it puts the mine theory on much shakier ground.

In many ways, the government of Spain is far and away the least likely perpetrator. Their fleet was woefully underprepared, to the point that a third of their heavy ships didn't participate in the war, and even those that did had very serious material problems.

As for "nationalist elements", I can't think of a better provocation offhand. Certainly nothing likely to generate the kind of public furor that Maine did.

Actually blowing up the Maine and killing most of her crew is definitely a maximal provocation, but as bean points out that's tough to guarantee. The median result for a torpedo or large mine would probably be the ship bottomed in the harbor with few casualties, and possibly not even that. Since the US never went to war with Yemen, that may not be enough. Though if you know Hearst et al will back your play, anything that results in Maine's keel touching sand will be spun as "Perfidious Spaniards sink Proud American Battleship" with lurid prose about sailors desperately trying to escape flooded compartments and leaving their doomed companions behind, etc.

On the other hand, this trades against just kidnapping some American girl and hinting that various unspeakable things might be happening to her, which is cheaper and more reliable and which similarly benefits from having the newspapers on your side. So that is an issue for the various conspiracy theories.