Iowa's refit at Hunter's Point after her first tour in the Pacific ran from January until mid-March of 1945. Besides the repairs to Shaft 3, she received an enclosed bridge (the original bridge had consisted of an open walkway wrapped around the front of the conning tower), updated radar for the Mk 37 directors, and new airplanes, SC Seahawks replacing OS2U Kingfishers.

USS Iowa in drydock at the beginning of her refit

The end of March was spent operating out of San Pedro Harbor, her future home, working up before going back to the front lines. She relieved New Jersey, due for a refit of her own, on April 20th, and was off Okinawa in support of operations there five days later. En route, the crew learned of the death of President Roosevelt, who they had carried across the Atlantic a year and a half previously.

Okinawa was in many ways the most brutal battle of the war for the US Navy. During the three-month campaign, beginning on April 1st, 1945, about 1,900 Kamikazes were launched against the fleet. Iowa got off very lightly, only firing a total of 56 rounds against Japanese attackers and taking no damage. Two of her escorting destroyers were not so lucky, although both survived the kamikazes that struck them. Iowa operated off Okinawa until May 10th, then returned to Ultihi for two weeks of training.

Iowa shortly after her refit. Note the changes to the bridge.

Then it was back to supporting the operations of TF 58, soon renamed TF 38 when the Fifth Fleet became the Third Fleet.1 June 4th brought another typhoon, this one fortunately not nearly as damaging as Cobra had been. Iowa herself was little affected, as the storm was small and Admiral Radford, commanding her group, was able to find a course that avoided the worst weather. Four days later, Radford's group launched an attack on airfields in southern Kyushu, although no major damage was recorded. Two days after the attack, William D Porter was sunk by a kamikaze while on picket duty off Okinawa.

TF 38 retired to Leyte Gulf, now one of the USN's forward fleet bases, to rest and refit after Okinawa, departing on July 1st for what proved to be the final assault on Japan. The first strike on the Tokyo area on the 10th took the Japanese by surprise. TF 38 then retired to the north, preparing to go after northern Honshu and Hokkaido, areas untouched by the B-29s that had been pounding Japan for months. On the 14th, 1,391 sorties were launched by the carriers, followed by a similar effort the next day. The most important result of this strike was the destruction of the ferry system between the two islands, cutting Japanese coal-carrying capacity by 50%.

USS Indiana bombarding Japan, as there are no pictures of any of the Iowas doing so

The 14th also saw the first bombardment of the Japanese mainland since 1864, although this honor went to South Dakota, Indiana and Massachusetts. Iowa's turn came the next day, along with sisters Missouri and Wisconsin, who had joined the Pacific Fleet in her absence. They rained a total of 860 16" shells (272 from Iowa) on the Nihon Steel Company and the Wanishi Ironworks, the second largest producer of coke and pig iron in Japan. The 170 shells that struck the plant itself are believed to have cost the Japanese two and a half months of coke production, and about two weeks worth of pig iron. In the surrounding city of Muroran, power was out for two days, water for a week, and the telephone system for two months.

Four days later, as part of a second attack on the Tokyo area, the three Iowas, accompanied this time by North Carolina and Alabama, went after industrial plants in Hitachi, 80 miles from Tokyo. The action report accurately stated that "Conditions for accurate gunnery were as difficult as might ever be expected." It was night, and the fire was from extreme range, at high speed, and with bad weather precluding any spotting. However, the 1,238 16" shells fired were still not particularly pleasant for the locals, who considered it more terrifying than the B-29 attacks they had been subjected to.

Iowa refuels from the oiler Cahaba, taken from carrier Shangri-La

TF 38 retired to the east, where it was resupplied in what Samuel Eliot Morison describes as "probably the largest logistics operation ever performed on the high seas", taking aboard 6,396 tons of ammo, 379,157 barrels of fuel oil, 1,635 tons of stores, 99 replacement aircraft and 412 personnel. Iowa herself received 238 16" projectiles, which must have been exciting to handle at sea. Air strikes followed on July 24th, 28th and 30th.2 Another typhoon brought an end to these strikes. This time, Halsey, having learned his lesson, avoided it, but was unable to continue the attack during the first week of August.

The fleet's actions during August are often overshadowed by the atomic bombs, dropped on the 6th and 9th, but they did considerable damage. The Japanese had planned to attack the B-29 bases in the Marianas by crash-landing 200 bombers carrying 2000 suicide troops on them. These were wiped out at their airfields by the aircraft of TF 38 on the 9th and 10th of August. After a brief refueling stop, Halsey launched a raid on Tokyo on the 13th, claiming over 250 Japanese airplanes destroyed.3 The follow-on raids on the 14th were cancelled after the first two waves were already in the air, as the Japanese had agreed to surrender.

Iowa, with Missouri alongside, transferring personnel

Missouri had been selected as the ship that would host the Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay.4 Iowa was to be alongside. The two ships entered Japanese waters on the 27th, three years since Iowa was launched. In that time, she'd covered 190,313 nautical miles. Two days later, Iowa and Missouri led the allied force into Tokyo Bay. There, landing parties were sent ashore to secure Japanese installations. A contingent from Iowa secured the last remaining Japanese battleship, the Nagato.

Crew from Iowa take possession of the Nagato. The flag in the foreground can be seen aboard Iowa today.

The most destructive war in human history ended on the starboard veranda of the USS Missouri on September 2nd, 1945, when General of the Armies Douglas MacArthur accepted the Japanese surrender. Missouri was anchored where Matthew Perry had anchored when he opened Japan in 1853, with Iowa 200 yards away. The occasion was marked by a flyover from the planes of the Third Fleet, whose carriers had been kept outside Tokyo Bay for fear of Japanese treachery.

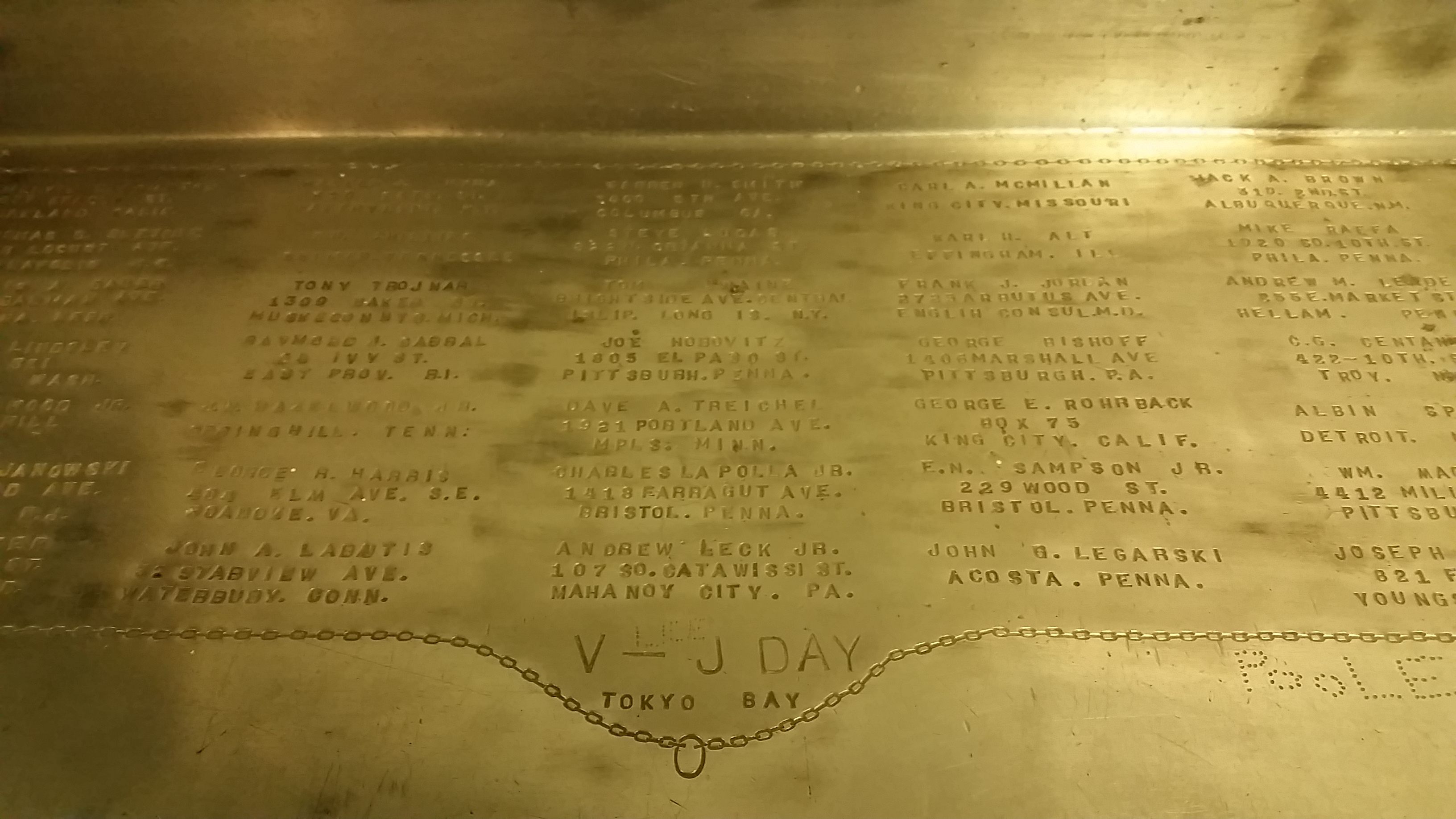

The bench in the machine shop5

Probably my favorite personal touch aboard Iowa is on one of the workbenches in the machine shop. On VJ day, the machinists on duty stamped their names into the bench by hand. The workmanship is incredible, and I loved taking guests down there, as you can almost feel the presence of the men who were there that day.6

Next time, I'll discuss Iowa's brief postwar career and her second commission, when she was called to war again.

1 The main US fleet in the Pacific was known as Third Fleet when Admiral Halsey was in charge, and Fifth Fleet when Admiral Spruance was in charge. The commanders were switched off occasionally to make sure both men, and their staffs, got to rest. ⇑

2 These strikes sunk the Japanese battleship Haruna, along with the hybrid battleship-carrier conversions Ise and Hyuga. ⇑

3 I suspect the real number was much lower. ⇑

4 Legend has it that Iowa would have been selected as the host for the surrender, if not for nepotism on the part of President Truman, whose daughter had sponsored Missouri. He was clearly blind to which ship was best, but it's an understandable delusion, and one I labored under for many years. ⇑

5 Thanks to Dave Way, Iowa's curator, for the photo. ⇑

6 I believe that it's possible for visitors to get down to the bench on the engineering tour, but I'm not sure that this is the case. ⇑

Comments

The bit about the proposed Japanese suicide attack on the Marianas is interesting. I'd never heard of that before, and now you have me wondering what the outcome would have been if they'd been able to go ahead. I'd like to think it would have been a Lesser Marianas Turkey Shoot, with unescorted Japanese bombers detected by radar and efficiently shot down, but the example of Operation Tan No. 2 suggests that the US in 1945 was rather complacent in its air defenses in areas nominally out of range of Japanese bombers.

The mechanical and navigational failures that claimed most of Tan-2's aircraft would still have been an issue, but there's a good chance that they could have put at least a few hundred "active shooters" and suicide bombers inside the fence on Saipan or Tinian.

Do you have any references on the Japanese plan?

I got the reference out of Morison V14, and I think it was mentioned in Downfall, too. I actually didn't remember Tan No. 2. Thanks for pointing that out. I'm sort of with you on US complacency, although I'd point out that US Intelligence had picked up on the Marianas plan. Presumably they'd be a little more alert than they were at Ulithi, where it doesn't look like they knew the raid was coming.

Silly question, but any idea why Missouri's #1 turret appears to be at maximum elevation while her #2 turret is trained as far aft as it is, and to the side that Iowa is on? (That second bit seems remarkably unsafe to me)

I'm not sure, but I can take a guess. Turret I's guns take up a fair bit of deck space on the forecastle, and if you have a bunch of people working there or even staging there, elevating them is going to make that a lot easier. I think Turret II is more of the same. Looking at Navsource's high-res version of the photo, they've got a lot of guys on the 01 level up there. The turret overhang takes up quite a bit of deck space, and rotating it like they did would free that up.

As for safety, I wouldn't be worried. "Don't point a gun at anything you don't want to destroy" is a good rule for small arms, because they are occasionally loaded even when you don't expect it, and it builds good muscle memory. But the guns on a battleship are kind of different. Powder is too dangerous to keep in the guns unless you have to, and if the breech is open, then you're entirely safe.