While Huascar was fighting the Esmeralda, another action was taking place off off Iquique. Another Peruvian ironclad, Independencia, had come with her, and had gone in pursuit of the Chilean Covadonga. This fight was, if anything, even more uneven than Huascar’s. Independencia was five times Covadonga’s size, armored, and three times faster.

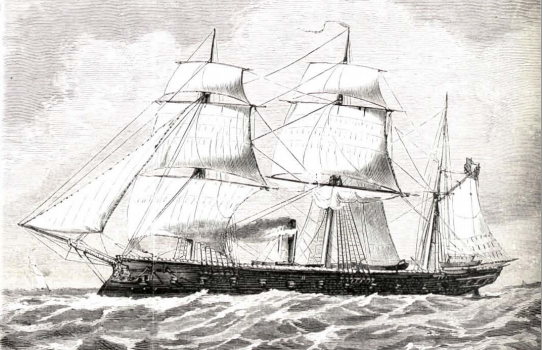

Independencia

Covadonga’s captain, Carlos Condell, handled her with skill equal to Prat’s. He stayed close inshore, using the fact that Covadonga drew considerably less water than Independencia to avoid the Peruvian ship. The fact that his gunnery was as good as Independenica’s was bad helped, too. Independencia tried to ram twice, both times taking careful soundings on the way in and aborting when the water grew too shallow. A third attempt occurred near Punta Gruesa, where Covadonga barely avoided grounding. Independenica’s helmsman was killed by a sharpshooter just as she touched the reef, and she ran hard aground. Covadonga rounded and poured fire into Independenica’s stern, setting her on fire.

Independencia aground off Punta Gruesa

Shortly thereafter, Huascar appeared, fresh from sinking Esmeralda. Covadonga turned south again, and Grau came alongside Independenica. After he determined that the crew was safe, he attempted to catch Covadonga, but soon determined that he couldn't close the gap before nightfall. He returned to Independenica, took the crew off, and burned the stranded ship. The whole action was a significant victory for Chile, and Prat's example inspired wide support for the war effort.

For the next six months Huascar held the Chileans at bay, capturing several ships and making a general nuisance of herself. The most famous capture was the transport Rímac, which was carrying an entire cavalry regiment. This caused a change of leadership, and of strategy, on the part of the Chileans. Cocharane's hull was cleaned by divers, and her machinery was given a thorough overall. When the work was completed, she was approximately a knot faster than Huascar.

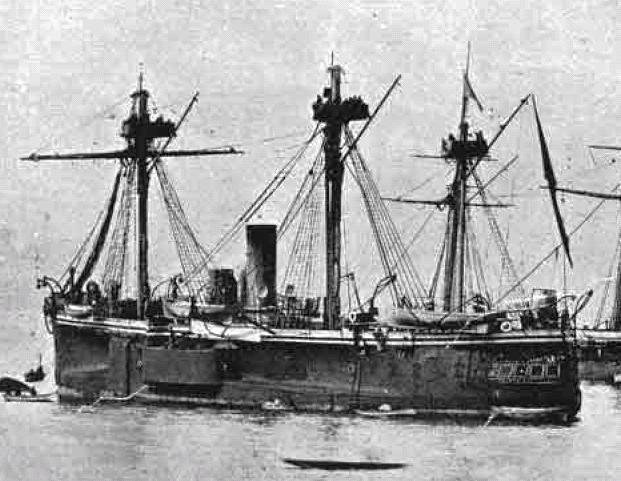

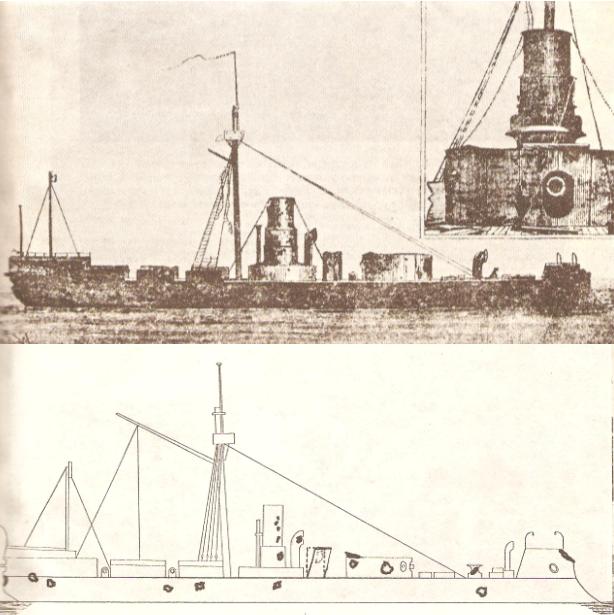

Cochrane

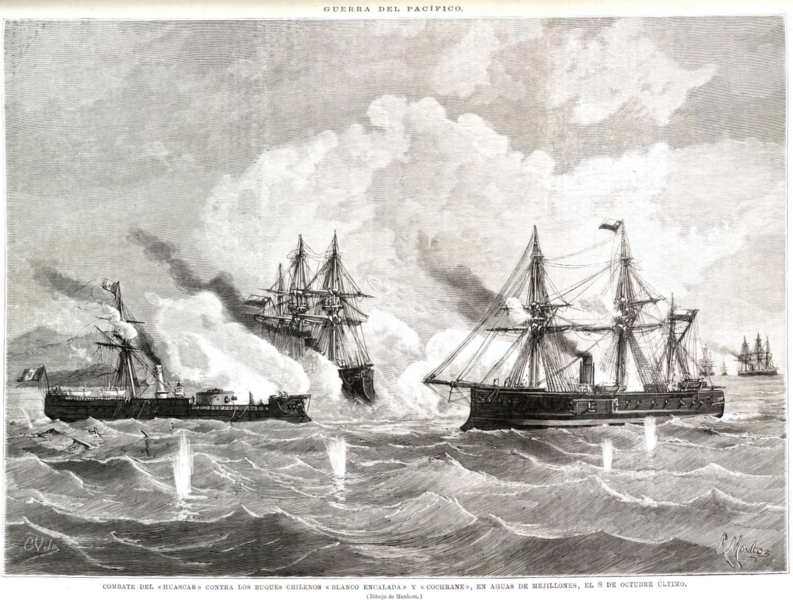

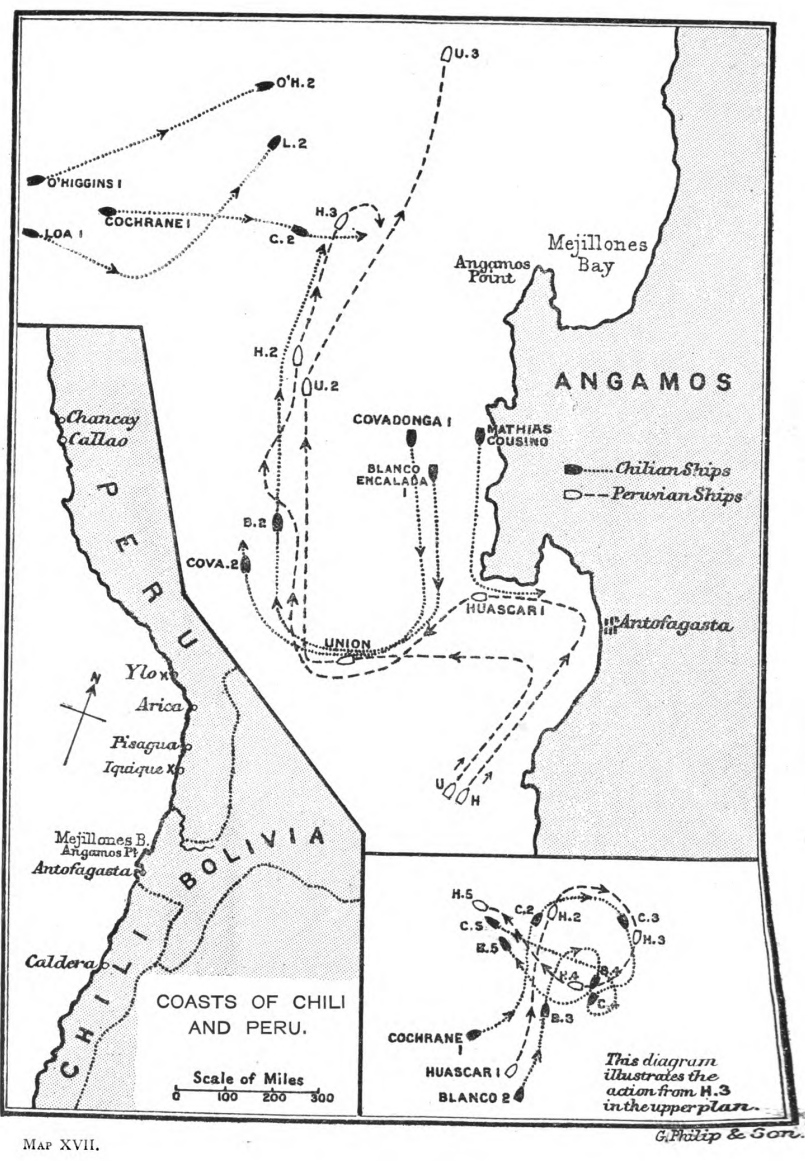

Matters came to a head on October 8th off Punta Angamos. Huascar first encountered Blanco Encalada, and ran north, away from the Chilean ironclad. However, the Chilean trap worked, and Cochrane pounced on Huascar. This time, it was clear that Huascar was outmatched. Not only was Cochrane more heavily armored, but she also had the 9" guns necessary to pierce Huascar’s armor. Huascar’s gunnery was better than it had been earlier, landing several hits, but none that were effective. Cochrane almost immediately landed a hit on Huascar’s belt that penetrated into the chamber under the turret, killing or wounding 12 men and temporarily jamming the turret.

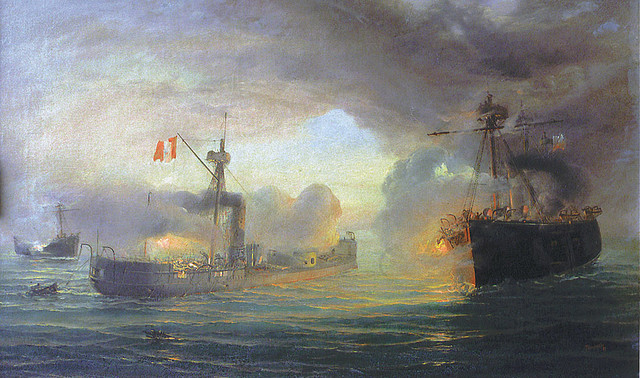

Cochrane engaging Huascar off Angamos

Huascar was in a difficult situation. Her turret could only bear on about a 130-degree arc on either beam, while the more maneuverable Cochrane sat in the dead zone aft. The Chileans had another advantage. Due to the short range, small arms fire was effective against exposed personnel, and the Chileans were able to dominate Huascar’s decks due to their taller masts and higher fighting positions. It became even worse when a 9" shell pierced Huascar’s conning tower, killing Grau. This shot also disabled Huascar’s steering gear, and she began to circle.1

The three ironclads in combat

A few minutes later, the turret was penetrated, taking the right gun out of commission. The gun crew was mostly killed or wounded, as was the acting captain. The Blanco Encalada finally arrived about an hour into the battle, and gave Huascar a brief respite by nearly ramming the Cochrane and forcing both Chilean ships to reposition. Huascar’s flag was soon shot away, and their was a brief lull until the Peruvians managed to hoist another. After another hit on her turret killed the third commanding officer, the Huascar’s former fourth officer decided to scuttle the ship. At this point, Cochrane was hit by a wild shot from Blanco Encalada, killing one man, the only Chilean death of the battle.2 The Peruvian flag was again shot away, and Huascar had stopped firing, so Cochrane and Blanco Encalada sent boarding parties. These parties secured the ship, although the Peruvians pointed out that because the flag had been shot down instead of being struck, Huascar had never formally surrendered.

A map of the action at Angamos

Huascar was repaired and placed into service by the Chileans, serving throughout the rest of the war. There were no more major naval battles during the War of the Pacific, as Chile had secured control of the sea at Angamos. This allowed her to defeat the Peruvian and Bolivian armies in detail. The war ended in 1883 with significant territorial concessions from both countries, including Bolivia's only connection to the Pacific. This is still a sore subject in Bolivia today, which has a navy at least in part in the hope that someday they will regain access to the sea.

Diagram of the hits on Huascar

After the war, Huascar remained in Chilean service. Refitted in 1885 and 1887, she gained new boilers and auxiliary machinery, replacing the manual winches previously used to traverse her turret. She was on the side of the rebels during the 1891 Chilean Civil War,3 who were eventually victorious after an eight-month struggle. In 1897, she suffered a boiler explosion and was decommissioned. In 1917, she was recommissioned as Chile's first submarine tender, serving in that role until 1930.

Huascar today

In 1934, Huascar was recommissioned again, this time as a heritage ship. She has been restored to her 1897 condition, and is a museum ship commemorating the naval heritage of both Peru and Chile in the Chilean port of Talcahuano. Huascar is one of the very few ships of her era still afloat today, and the Chileans have apparently done an incredible job of preserving her. Some day, I want to see her for myself.

1 This was only one of the 3 or 4 times the steering gear was disabled during the battle. Huascar’s crew fought magnificently during this action, despite taking an incredible amount of fire. 35 of the 197 men aboard died, and she took 27 hits by heavy projectiles. ⇑

2 Norman Friedman suggests that one of the main reasons Chilean gunnery was so much better was because the guns of their central-battery ironclads were much easier to handle in action. Turrets, particularly manually-traversed turrets like the one aboard Huascar, were very difficult to point accurately during this era, and it wasn't uncommon to leave the turret stationary and turn the ship, then fire when the gun was pointing at the target. The guns of the central-battery ships were much lighter and could be pointed individually. ⇑

3 The previous one was in 1829-1830. ⇑

Comments

If wikipedia is to be believed, Independencia's lmsman was killed by a sharpshooter from Covadonga. It seems a curious design discrepancy in an ironclad for the helmsman, and helm generally, to be unprotected against even rifle fire. Monitor and Virginia I know both put the helm under armor; were fully exposed steering positions common in early seagoing (and thus sail-rigged) ironclads?

While doing reading for this, I found out that Huascar at least had multiple steering positions. At one point, shifting from the exposed to the protected position nearly got them in trouble, although not enough trouble to make it into the posts. I'd suspect that the same was true of Independencia, and the captain didn't want to retreat to the conning tower while trying to ram someone in shoal water. There probably wasn't a good way to talk to the protected helm while he was on deck. Or maybe they just didn't have time.

Bean - I tried to make this comment on SSC but it got eaten by the spam filter somehow. Not directly related to this post, but...

I have noticed that several early ironclads (the I-know-they're-not-that-important-but-still Monitor and Virginia being good examples) have barely any freeboard. All dreadnoughts, by comparison, have extremely high decks, as do all modern warships. I'm sure this is a very stupid question but: why? Is this necessary? My very limited understanding is that freeboard gets you three things:

1) reserve bouyancy

2) high sensor positions -> longer horizons (but strictly speaking this just implies tall masts/superstructure)

3) seakeeping ability (Monitor foundered in a storm, and my understanding is that just heavy waves in a high sea are bad.) I am unclear what fraction of this are a) the dynamical system of the ship rocking is more stable when it's taller b) the simple fact you don't want waves on the deck.

Working against this, in my mind, is that a ship that is barely above the water is going to be harder to hit and harder to see (I'd expect a smaller radar signature too...) Yes, you'd need tall masts (or in a very modern ship tethered drones?) and don't ask me what to do with a giant AN/SPY-1 phased array radar, but still.

Is it really not possible with modern tech to give a ship with small freeboard good stability with proper design of the underwater hull/computer aided stabilization? Reserve bouyancy seems dubious too (ballast tanks maybe?) I am given to understand modern subs roll miserably on the surface, which says "no", but I don't have a good sense as to why. (If you can link to a good simple explanation of the dynamical-systems aspect I'd love to see it.)

I'm sure this is a very dumb idea, but it's not 100% clear why.

@Andrew The Great Freeboard Debate is covered in some detail in the Pre-Dreadnought column I just finished writing, but that's not going to be up for a couple weeks. Yes, it's necessary. Not so much on the sensor side, but primarily for stability and seakeeping. Stability starts to go away when the deck edge submerges (why is another column I'm working on) and it's hard to work/fight the ship when you have waves on deck.

Harder to hit only if the missile doesn't have a pop-up mode. Harder to see, sure, but the drawbacks are too great. If you sacrifice seakeeping to stealth, you get a Zumwalt.

Computer stabilization is not something you want the ship to rely on. Backups are big and heavy, and you don't want the ship turning turtle in a storm if it goes out.

Underwater hull shape can't help because the first-order determinant of stability is the shape of the hull at the waterline. The best place to start is to google "Metacentric height". It's also in the green naval engineering book, IIRC.

The last problem is that modern warships are basically volume-limited. With battleships, the big problem was figuring out how to cram all the important stuff in without the ship being too heavy and sinking. Now, it's a matter of finding space for everything. Even back in the 1860s and 1870s, low-freeboard ships were noted for being cramped (look at my comments on Devastation), and it would be far worse today.

Is there a known reason for the disparity in gunnery performance?

Better training on the part of the Chileans, as far as I know. Chile had professionalized their military, and Peru hadn't. That's apparently one factor that lead to the war.

I've read that Huascar fired a wire-guided torpedo on 27 August 1879, only for it to malfunction and nearly hit her, possibly followed by them being disposed of as too dangerous. (Ironically for a time when one claimed reason to prefer guided torpedoes was that they were less of a friendly fire hazard than the unguided kind.)

It seems plausible that this was the first time a guided weapon was fired in anger, but my source doesn't claim either way, and does mention a similar (but separately developed) one existing in 1869 Russia.

Both apparently had a range of a few miles (i.e. longer than anything else of the time was likely to actually hit at) but a slow enough speed that an aware target could outrun them.

I don't know if their slowness was a result of them needing to show enough at the surface (incurring wave drag) to be visible to the operator, or if an unguided torpedo of that range would have been similarly slow.

Maybe there's a plausible alternate history where these become dominant and the fire control era (as this blog knows it; there might be a similar amount of work put into better-than-full-manual guided weapon control) never happens??? Though the number of failed attempts at least sort of suggests not.

Yeah, I missed that when I wrote this, probably because my main source was almost contemporary. But looking into it, I found two sources that mention it, one at some length. I will dig into it and edit it in.

Also, may I ask what source to see if it is one of the two?