In early April, 1982, Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands and South Georgia, isolated specks of rock in the South Atlantic. Their sovereignty had been disputed between Argentina and Britain for a century and a half, and Argentina expected Britain to simply accept their conquest. They were sorely disappointed, as the British instead mobilized their fleet, sending men and ships south. On April 20th, while the majority of the amphibious group was still frantically sorting itself out at Ascension, the British finally abandoned efforts to find a diplomatic solution to the Argentine forces on South Georgia, and decided to eject them by force. There were several reasons for this decision. First, unlike the Falklands, Argentina’s claim to South Georgia was basically nonexistent under international law. Second, it would give the British a sheltered anchorage much closer to the Falklands than Ascension was. Third, it was lightly defended and out of range of Argentine air attack.1

HMS Antrim off South Georgia

Operation Paraquet, as it was known, was conducted on a shoestring. The landing force was made up of 42 Commando,2 D Squadron 22 SAS,3 and 2 Troop SBS.4 As all the proper amphibious warfare ships were still around Ascension, they were carried by the destroyer Antrim, our old friend Endurance and the tanker Tidespring.

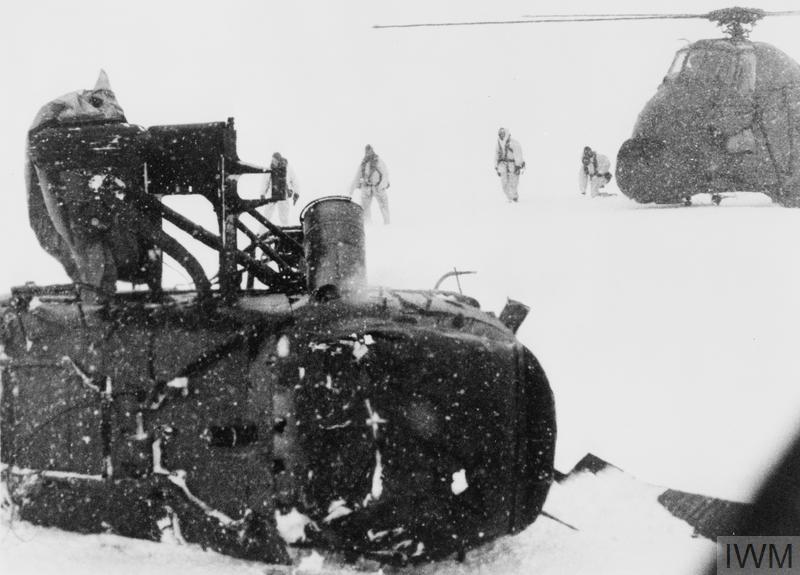

A photo taken during the SAS recon mission

The operation didn’t get off to an auspicious start. The initial plan had the SAS and SBS reconnoitering Grytviken and Leith, where the Argentine forces were believed to have stayed.5 Three Wessex helicopters from Antrim and Tidespring attempted to land an SAS unit on Fortuna Glacier 10 miles from Leith early on the 21st, but the weather turned sour, and they were driven off. A second attempt in the early afternoon succeeded, despite truly awful flying conditions. That night, a storm battered the ships and rendered the position of the 12-man SAS party on the glacier untenable. The three helicopters reached them on their second attempt the next morning, but while loading the troopers, snow began to blow around them, reducing visibility. One of Tidespring’s helicopters tried to take off, but the pilot became disoriented in the white-out and crashed, putting the helicopter on its side. The crew and passengers were mostly fine, and sorted themselves out between the other two helicopters, which took off without incident.

A crashed Wessex on Fortuna Glacier

On the way back to the ships, the second helicopter from Tidespring hit a ridge on the glacier that Antrim’s Wessex had avoided, skidding and falling on its side as well.6 Everyone aboard survived without major injury, but there was no way that the remaining helicopter, already badly overloaded, could pick them up immediately. It returned to Antrim, unloaded, and attempted to return for the survivors of the second crash. As they probably expected by now, the weather was too bad on the first attempt, and they had to wait an hour or so for a gap. Finally, an hour before sunset, the lone Wessex returned to Antrim with the remaining SAS men and aircrew. The operation, though without loss of life, had destroyed most of the transport helicopters available to the British. Attempts to land SAS and SBS troops by boat from Antrim and Endurance that evening and the next day were no more successful. Newspapers began to leak the presence of the British near South Georgia, and on the 24th, Endurance was sighted by an Argentinian Air Force Boeing 707.

USS Catfish before she became ARA Santa Fe

Matters were made worse by the appearance of the Argentine submarine Santa Fe that day, dispatched with reinforcements for the garrison. She unloaded at Grytviken, then sailed to cover the coast. She sighted Endurance, but for unknown reasons declined to attack.

The news wasn’t entirely bad for the British, though. The 24th also saw the arrival of the frigate HMS Brilliant, with two Lynx helicopters. These anti-submarine birds couldn’t match the carrying capacity of the crashed Wessexs, but they had the avionics to operate safely in the dreadful weather of South Georgia.

Antrim’s omnipresent Wessex, now at the Fleet Air Arm Museum

At 0900 on the 25th, Santa Fe was on the surface off Grytviken when she was spotted by Antrim’s Wessex. Her captain chose to remain on the surface, in hopes of making her immune to homing torpedoes.7 Unfortunately, the Wessex was armed with depth charges, and the first British air attack on a submarine in 37 years damaged Santa Fe badly enough that she was unable to submerge.

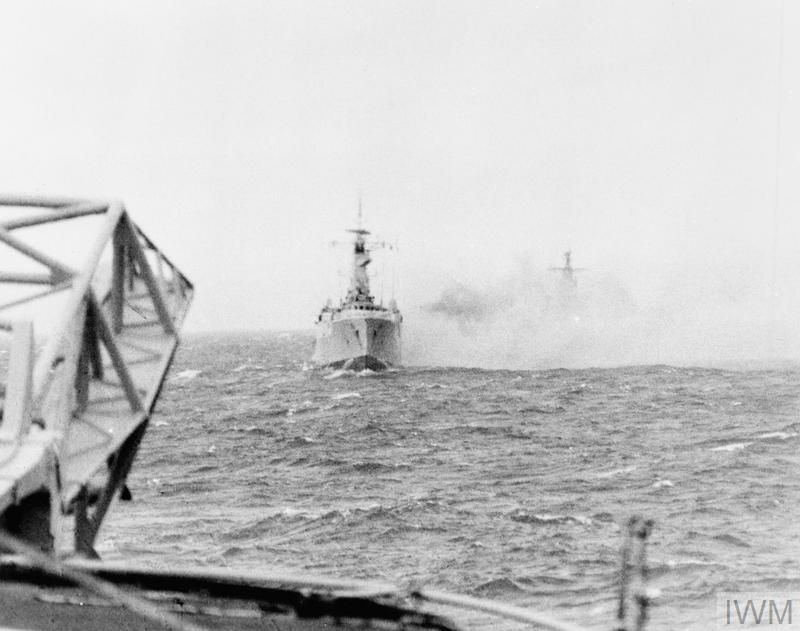

HMS Brilliant, seen from Iowa during Ocean Safari 858

Santa Fe turned to run for Grytviken, but was pursued by the British helicopters. The Wessex used its door-mounted machine gun, while one of Brilliant’s Lynxes joined in with a homing torpedo. For whatever reason, the torpedo missed, and the Lynx added its machine gun to the fray. The Wasps from Plymouth and Endurance headed towards the submarine, armed with AS.12 missiles. Endurance was much closer, and the first missile from her first Wasp managed one hit on Santa Fe’s sail, while the second missed. Because of how close Endurance was, this helicopter managed to return, rearm, and launch a second attack before Plymouth’s helicopter even got into range. This attack resulted in another hit from two missiles, while the chopper from Plymouth got a hit with its only missile.

Westland Lynx

At this point, Endurance’s second helicopter had arrived, and made another hit, although only on the empty fiberglass portion of the sail. The Argentines, both on the submarine and ashore, had begun to fire on the helicopters with machine guns and anti-tank rockets, and the next attack, by Endurance’s first Wasp, was the last. Fortunately, one of the missiles struck near the periscopes, destroying them and other equipment in the sail. Two hours after she was spotted, Santa Fe came alongside the pier in Grytviken, slowly sinking and on fire.

Royal Marines on South Georgia, 1982

The British commander decided to launch the assault on South Georgia immediately, despite the fact that the majority of 42 Commando was 200 miles away onboard Tidespring. The 75 troops available, a mix of SBS, SAS, and Royal Marines, were well armed and expertly trained, and the ability of the warships offshore to deliver fire support would hopefully tip the balance in their favor.

HMS Plymouth bombarding Argentine positions

The first group, a gunfire spotting team, went ashore at 1420, only half an hour after they’d been briefed on the operation. They began to drop 4.5″ shells on the Argentine positions, covering the arrival of the assault troops half an hour later. They were shuttled ashore in Antrim’s Wessex and the Lynxes from Brilliant. The force quickly marched on Grytiviken, running through a minefield without loss and demoralizing the defenders. Despite outnumbering the British, the Argentine garrison surrendered at 1705, and the British commander reported back with the famous message “Be pleased to inform Her Majesty that the White Ensign flies alongside the Union Jack in South Georgia. God save the Queen.”

Astiz signing the surrender for the troops at Leith Harbor

There were still Argentine troops at Leith Harbor, under the command of Alfredo Astiz, a thoroughly nasty character who played a key part in the “Dirty War” against opponents of the Junta. He attempted to trick the captain of Endurance into landing in a helicopter on the soccer field, under which was buried a large explosive charge. Fortunately, the British decided to come by sea instead, and the only casualty of the entire battle was an Argentine submariner who lost his foot during the attack on Santa Fe.

British troops guard Santa Fe

On the 27th, while the British were moving Santa Fe to clear the only pier in the harbor, tragedy struck. Some of the Argentine crew were enlisted to help out, and told that any attempt to scuttle the submarine would result in them being shot. Unfortunately, Petty Officer Felix Artuso tried to operate a control the British believed would flood the boat, and was shot and killed by a sentry when he ignored orders to stop.

The funeral of PO Artuso

At that point, it was just a matter of cleanup. The Argentinians had booby-trapped most of the buildings on the island, and were ordered to clear the most dangerous examples, Astiz’s work being particularly nasty. The full scope of his activities as a torturer during the government’s Dirty War against internal opposition was beginning to come out, and the governments of France and Sweden requested he be questioned for involvement in the disappearance of their citizens. The British refused, citing the Geneva Convention.9

Alfredo Astiz

A final note of humor came from a newspaper editor who ordered one of his correspondents to proceed within 24 hours to South Georgia and interview the commander there. The correspondent, currently off Ascension and unable to even get ashore there, was obviously unable to comply, and the message resulted in much amusement throughout the task force.

Grytviken Harbor, 1982

The liberation of South Georgia was the first clash between British and Argentine forces on relatively equal terms, and it set the pattern for the rest of the war. Despite a position that was, on paper, superior, the Argentinian solders were unable to exploit their advantages, while the British took full advantage of all the tools of modern warfare. Their ability to react quickly and professionally to changing circumstances allowed them to overcome early failures and win the victory. Next up were the Falklands themselves, which would not fall so easily.

1 I’ve written a glossary to make it easier to keep track of terms in this series, and the full list of posts is here. ⇑

2 A battalion-sized unit of Royal Marines. ⇑

3 About 65 men of the British special forces unit. ⇑

4 A dozen or so men from the British maritime special forces. ⇑

5 The British were still in contact with several of the British Antarctic Survey teams on the outlying parts of the island, and they hadn’t been disturbed. ⇑

6 Antrim’s helicopter was an anti-submarine Wessex HAS3, equipped for all-weather flying. The helicopters embarked on Tidespring were Wessex HU5s, set up for carrying troops and lacking a comprehensive suite of instruments. ⇑

7 The active homing systems on most ASW torpedoes are confused by reflections from the surface, but many have a backup passive mode to deal with this. ⇑

8 Due to absurd British copyright laws, public-domain pictures of RN warships are much harder to come by than those of their USN counterparts. There were two photos of Brilliant in Wikimedia, both taken by the USN during Ocean Safari 85. The other one gives a better view of Brilliant, but I couldn’t resist using this one for obvious reasons. ⇑

9 Astiz would be repatriated to Argentina, and didn’t stand trial for his crimes in Argentina until 2011. (In 1990, he was convicted in absentia for the disappearance of a pair of French citizens.) Happily, he is now serving a life sentence. ⇑

Comments

That photo Royal Marines on South Georgia, 1982 looks fake.

I think the problem is that the mountains in the background are in focus, but so are the men in the foreground. Unless of course this was taken with some super advanced camera with an amazing depth of field.

The wikimedia page says that it’s a colorized black & white image. Also, I’m using a lower-res version, which may be making the background look sharper.

One of the things that piqued my interest was the Santa Fe story. Are all submarines that robust or was she just unusually lucky? She was hit by a depth charge, at least (if I’m counting correctly) 5 missiles and it managed to stay afloat and make it to the pier. I kind of thought that the moment the sub surfaces and is spotted from air it’s game over (which it was, essentially, though it took more time than expected).

Also the actions of the British in relation to the boat don’t make sense. First they were trying to sink the boat, than (while already half-sunk near the pier) she was disabled by a British diver further, it’s already evident that the sub is a hunk of junk. Why stop Argentinians from scuttling the boat themselves, considering that when it was all over, Brits did that themselves? The only credible reason I can think of is that a sub sunk by the pier can be raised relatively easily and brought back into the fleet, but, in all fairness, Santa Fe is not that big of an asset even when fixed, and fixing it would deepen the hole in the budget of Argentine after the war. All in all, it doesn’t seem to be worth of all the attention it was devoted.

All submarines are that robust. They have to be, because they’re designed to withstand the pressure of diving. The fact that they’re essentially fairly well armored is a nice bonus. The depth charge wasn’t a direct hit. It just damaged enough stuff to keep her on the surface. (Probably blew some valves open, which would let in too much water if she dived.) The missiles were anti-tank missiles, which aren’t that effective against warships. And most of the missiles hit the sail, which is mostly empty.

I’m not sure what you’re talking about with the diver. I don’t remember any diver being involved.

The reason for moving Santa Fe is not Santa Fe. It was the pier. She was blocking the only pier in Grytviken, which the British wanted to use for themselves. If the Argentinians had scuttled her at the pier, they would have had to do more work to get her out of the way.

@Inky: I think you are overestimating British knowledge levels in the moment. Before they captured the sub, they couldn’t even get an observer close to judge the damage, due to the machine guns. In addition, they clearly didn’t have any submariners with the force to help with assessment of damage, and they didn’t know if they would win the rest of the war as completely as they did.

While the ship was still Argentinean, all they really knew was ‘not damaged enough to surrender’. Wasn’t clear what the mission was, either, whether it was meant for sea denial or to bring in reinforcements. Maybe it was delivering something then needed a little repair and would return to sea to try to drive off the British force. If the depth charge had missed and the machine guns were sufficient to keep the helicoptors away then it clearly would need continued attack.

After the capture, I’m sure they didn’t know how much work to repair, let alone what bargaining chips the diplomats would need in the final settlement. Could easily imagine something like ‘your last two garrisons surrender and we give back all the ships and crews we captured.’. Or if things had gone really sideways, ‘you let us retreat and we don’t scuttle your submarine’. Probably they didn’t know how badly the sub was damaged until they had won and had the leisure to get some submarine engineers to visit and assess the damage. Why limit your options prematurely?

As for the first question...keep in mind that ‘unable to submerge’, if it happens while submerged, means either emergency surfacing or immediate death. Emergency surface might not even be possible. Against a force that is not a shoestring, a surfaced sub can be shot at from a range at which it can’t retaliate, which is never a good spot to be in.

@David W

I wouldn’t necessarily assume that they didn’t have any submariners with them. It’s not uncommon to have a guy or two on rotation from another branch, to make sure that people know what other branches do, and can draw on their expertise.

But yes, they didn’t know how bad the damage was before they captured the submarine. Afterwards, the primary driver was the need to get the pier clear. If she’d sunk somewhere else, they would have left her, and possibly properly scuttled her. As it was, they were afraid the crew would flood the entire boat, which would have made getting her out of the way a lot harder. (I suspect the depth charge damaged valves in the ballast tanks, which were slowly leaking. Valves can be adjusted and/or ballast tanks pumped out. If the whole sub floods, she’s no longer able to move under her own power, which makes getting her out of the way a lot harder.)

I assumed if they did have submariners along who could be spared from their duties, they would have left the Argentinean crew on shore during the pier clearing manuever. I guess it’s immaterial to the decisions about the disposition of the sub whether the force had no submariners or simply could not spare them for the time it would take to judge the sub uneconomical to repair.

A submarine isn’t a car. They don’t all work the same, and you can’t just hop in and drive one. The British almost certainly had someone who could go over the boat and get a pretty good idea of what sort of shape she was in. (As far as that mattered, which was very little.) But they didn’t have anyone who knew how to drive her, so they had to use the Argentinian crewmen.

But they do it in U571.

:-p

There were submariners available on HMS Brilliant. According to the report of the RN Board of inquiry into PO Artuso’s death, three officers were sent from Brilliant to “examine the submarine for intelligence purposes and make it safe”. One is described as a “submarine specialist”, one had been a sonar maintainer on a Polaris SSBN for 6 months (and had no experience of conventional submarines at all) and one was not a submariner but had diving and demolitions qualifications.

The second officer (the one with some, but limited submarine experience) misidentified the low pressure air controls as the main vent levers and ordered the Royal Marine guard not to allow PO Artuso to touch them. When he did (having been ordered to do so by an intercom that the Marines could not hear), he was shot.

For more detail, the report can be found here

Thanks for tracking that down. That’s pretty much what I expected, but it’s nice to have confirmation.

(As for why you use the original crew, let’s say that guy #2 got the low-pressure air control and the flood valve switched. Try it with a British crew, and you have a scuttled boat.)

@bean

About that diver - I found the mention in Wiki, no source listed, so take as it is.

Thank ya’all for all the analysis, rather enlightening.

Ah. I’ve checked Royal Navy in the Falklands War, which does mention the diver, but it’s after the sub was moved away from the pier. That makes a lot more sense. It’s not mentioned in the main Operation Paraquet article, and it got pushed out of my mental buffer as irrelevant when I wrote the post in the first place.

As John Schilling once said, “Go not to the Wikipedians for counsel, for they will say both no and yes and Citation Needed”.