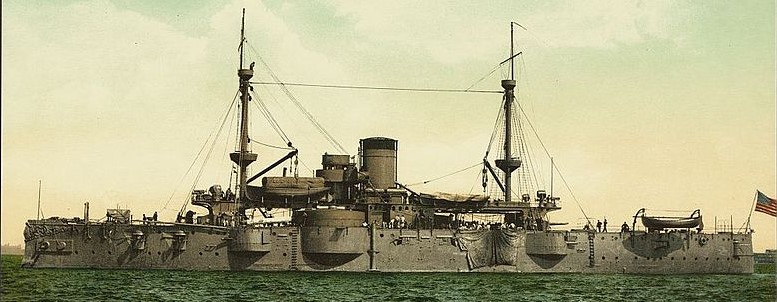

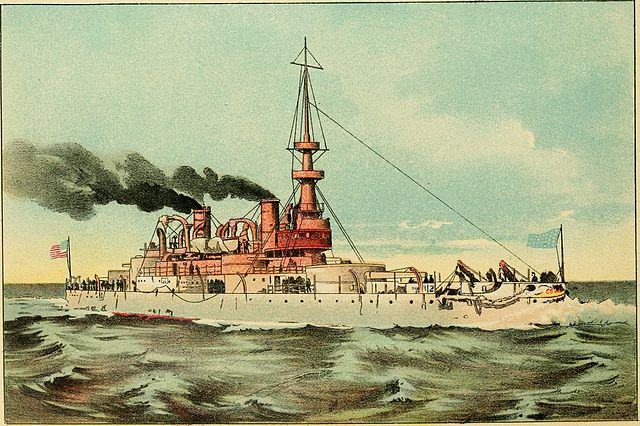

After the end of the American Civil War, the US quickly went from having one of the world's most powerful navies to one of the least powerful. From 1865 to 1882, Congress left the navy to rot, and the US was soon behind such naval giants as Chile and Brazil. In 1882, an advisory panel recommended the construction of new ships, including battleships in 1885. The resulting ships, Texas and Maine,1 were second-class battleships of the generation immediately proceeding the Royal Sovereign, with en echelon turrets. Texas had two single 12" guns, while Maine had twin 10" guns. The secondary battery was 6 6" guns, although American industry was not up to producing 6" QF guns at this point, so the guns were not quick-firing. Both had armor protection over only a limited area, and would have been very vulnerable to QF gunfire. They took almost 9 years from contract to completion, and were thus obsolete before they entered service. Because of this delay, and of their origins as second-class ships, they had little influence on later US designs.

USS Maine in Havana Harbor before the explosion

Congress was still being stingy with funding, and in 1889, just before leaving office, Representative John R. Thomas managed to pass an appropriations bill mandating the construction of an "armored cruising monitor" of his own design. This would have been a low-freeboard ship with a twin 10" turret forward, a 6" gun aft, and a 15" dynamite gun2 in the bow. Thomas was a lawyer, not a naval architect, and the new Secretary of the Navy, Benjamin Tracy, managed to kill it off before it could turn out to be about the most useless ship ever built for the USN.

USS Texas

Tracy was a supporter of Alfred Thayer Mahan, who published his seminal book, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, in 1890. Mahan advocated a large and powerful fleet as the only way to gain control of the sea and accomplish national objectives. This was in direct opposition to the traditional US strategy of coastal defense and commerce raiding, but it soon gained wide acceptance.

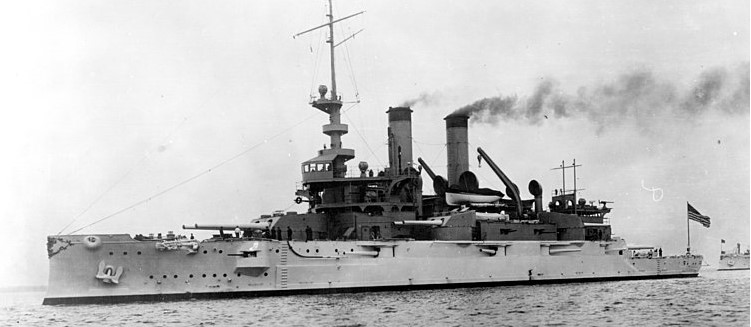

USS Indiana (BB-1)

The initial plan had the US fleet split into two parts, one for coastal defense, the other to carry the war to enemy waters. The first three modern US battleships, the Indiana class, were for the former role. They were low-freeboard ships with two twin 13" turrets. Their secondary armament was decidedly unusual, as a result of American industrial limitations. The US couldn't produce QF guns, so the secondary armament was 4 twin 8" turrets, with 4 non-QF 6" guns backing them up. The 8" was considerably faster-firing than the 13", and it could penetrate armor intended to stop 6" fire. At only 10,000 tons, these ships were seen as packing considerably more firepower than contemporary British ships on a smaller hull.3 In service, however, they were not particularly successful. The USN discovered why the British had abandoned low-freeboard designs, particularly as the Indianas were badly overloaded, to the point where their main belt was submerged at normal displacement.4 This was made worse by unbalanced turrets, which sunk the belt even further when trained on the beam. The small hull and heavy armament also lead to serious problems with blast interference.

USS Iowa (BB-4)

The next ship USS Iowa (BB-4), was intended as the prototype for the seagoing battle fleet. To gain the necessary range, the 13" guns had been replaced by 12" weapons, and the 6" secondaries had been replaced by the first US QF guns, although they were only 4" weapons. A high forecastle improved seakeeping, and the longer hull reduced blast interference. Most importantly, the design displacement now included a reasonable amount of coal. Harvey armor was introduced on Iowa, which also helped hold displacement down.

USS Kearsage (BB-5)

After Iowa was authorized in 1892, there was a three-year gap before the next battleship was ordered. The two units of the Kearsage class5 departed entirely from the original plan. They were a compromise, the size of Iowa, but with only 3' more freeboard than the Indianas. The US had finally gotten a 5" QF gun into production, and to make room for the 7-gun casemates on each side, the designers had to get creative with the 8" guns. Placing them on the centerline would allow a single turret to substitute for the two wing turrets of previous battleships, but centerline space was limited. So the 8" turrets were mounted on top of the 13" turrets, to produce the superimposed turret. In theory, this was a very good idea. The 8" guns were free of blast from the 13" gun, and the faster-firing 8" gun could be aimed at different targets while the 13" was being loaded. In practice, it worked about as well as you'd expect.

USS Illinois (BB-7)

At this point, the US was beginning to get seagoing experience from the Indianas, and convened a board to analyze the requirements of future battleships. The coastal battleship was rejected, as the USN had begun to focus on the threat of a European power seizing bases in the Caribbean, which required ships with long range and good seakeeping. The US had finally gotten a 6" QF gun, and the 8" was duly discarded.6 The resulting Illinois class had 14 6" and 4 13", with the 13" guns in turrets with what became the signature sloped faces of American heavy gun mounts.

USS Missouri (BB-11) of the Maine class

After the Illinois class of 1896, no battleships were authorized in 1897. In 1898, war broke out with Spain, and another three battleships were authorized. The Maine class were based on the Illinois class,7 beating out an improved Iowa. A number of detail improvements were made, most notably the replacement of the 13" guns with improved 12"/40s using smokeless powder. Krupp armor was used for the belt, and improved boilers allowed them to make 18 kts, 2 kts more than their predecessors. The ships had to be lengthened for this, which allowed an extra pair of 6" guns.

In the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, the US had gained an empire, and needed the ships to defend it. It had also gained combat experience with Texas, the Indianas, and Iowa. This resulted in the return of the 8" gun, which had put on a good showing at the Battle of Santiago. Nobody seems to have noticed that the 8" in question was functionally obsolete, and only good compared to the slow-firing 6" guns mounted on the ships in action.8

USS Virginia (BB-13)

The resulting Virginia class had 8 8" guns, four of them in superimposed turrets. This was not a good decision. Improvements in gunnery meant that the 12" fired almost as rapidly as the 8", removing the gaps that the original superimposed turret had been meant to exploit. On the other hand, the war meant that Congress authorized bigger ships, giving the Virginia's designers more flexibility. Their armor was improved, speed was raised to 19 kts, and a dozen 6" QF guns backed up the 12" and 8" guns.

USS Connecticut (BB-18)

Despite the poor rationale, the time was ripe for the return of the 8". Combat ranges were increasing, and armor effective against 6" fire was spreading across the sides of ships. The Virginias served to kick-start the development of the semi-dreadnought, breaking navies out of the 12"/6" standard common at the time. The next development, the Connecticut class, was by far the best of the US pre-dreadnoughts. Displacement rose to 16,000 tons, a 10% increase over the Virginias, the superimposed turret was discarded, and the armament was four improved 12", eight 8" in twin turrets and twelve 7" in casemates. The use of the 7" gun seems rather bizarre, with only an inch separating it from the next gun up. This was apparently because the 7" shell was just within the capability of a single man to handle, making it the largest possible gun capable of really rapid fire.9 The ships were a knot slower than the Virginias, but protection was improved.

USS Mississippi (BB-23)

Many in Congress and even within the Navy felt that the Connecticuts were too big, and that larger numbers of smaller, cheaper ships would be a better choice.10 The result was the Mississippi class of 13,000 tons. The loss of 3,000 tons meant a knot less speed, less belt armor, shorter range, worse seakeeping and four fewer 7" guns. The two ships were unpopular even before they were completed in 1909, and five years later both were sold to Greece, which allowed the USN to order a third unit of the New Mexico class dreadnoughts.

The Great White Fleet

The construction of these ships had turned the United States Navy from a backwards joke into one of the world's leading naval powers. To highlight this, Theodore Roosevelt sent 16 of the ships around the world as part of his famous Great White Fleet between 1907 and 1909.11 This cruise was a diplomatic triumph, and gave valuable experience as the US began to look at operations over the great distances of the Pacific.

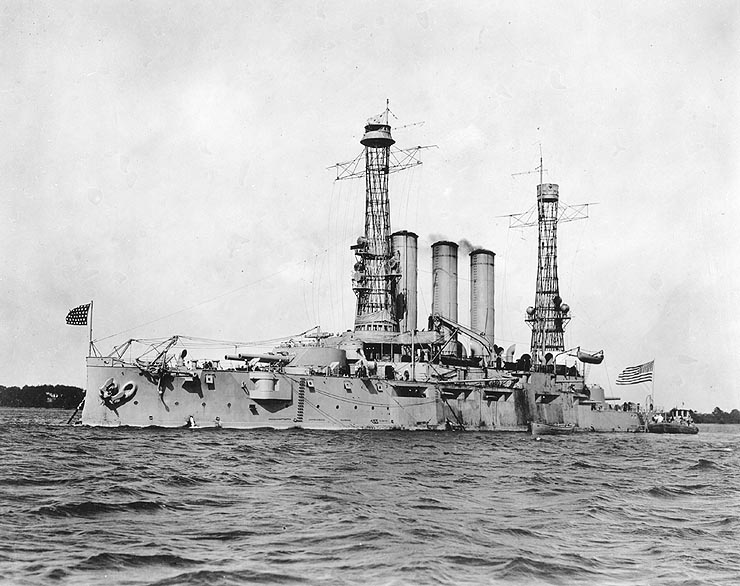

USS Maine (BB-10) fitted with cage masts

The pre-dreadnoughts were rapidly made obsolete by the construction of American dreadnoughts beginning with the South Carolina class. In about 1910, they were refitted with the signature US cage masts.12 They soldiered on through WWI, serving in various secondary roles, until 1923, when the last units were retired under the Washington Naval Treaty.

In only two decades, the US Navy leapt from obscurity to take its place among the world's leading navies. This was mostly due to the construction of a series of pre-dreadnoughts largely forgotten today, although they were innovative and set the stage for their far more famous dreadnought descendants. Anyone who wants to learn more about these ships should get a copy of this book.

1 Maine was originally classified as an armored cruiser, but was in practice very similar to Texas. ⇑

2 This was an attempt to avoid the problems of explosive shells by launching them with compressed air ⇑

3 The 8" guns were also seen as a major advance in the US and abroad, as most understand guns only by caliber and not other factors. Friedman, in US Battleships, compares this to the Soviet adoption of anti-ship missiles. These can be seen as inefficient naval aircraft used by those without carriers. In western service, these missiles would only be adopted if they were superior to existing systems, and the Soviet missiles were analyzed in that light. The extension to Chinese military choices today is obvious. ⇑

4 The design displacement included 400 tons of coal, but they had bunker space for 1,200 tons and rarely went to sea without that much. ⇑

5 Kearsage was the only American battleship not named for a state. She was named after a famous sloop from the Civil War, which was wrecked just before she was laid down. Congress passed a special exception to the legal requirement that battleships be named after states. Interestingly, that requirement is still on the books, in 10 USC 7292. ⇑

6 The US estimated that the 6" would provide about three times the weight of fire per unit time. ⇑

8 As Norman Friedman said of this, "Throughout the history of modern warships, however, combat experience, no matter how objectively irrelevant, has had enormous impact." ⇑

9 The 7" gun is credited with 4 rds/min, as opposed to 2 rds/min for the 8". Most navies considered 6" the maximum caliber for single-man handling, but the USN apparently believed that it could get stronger sailors from the farm states. ⇑

10 This is a fairly common belief, but it usually just results in bad ships. Examples come from basically every navy. The situation is even worse today, as air is free and steel is cheap, but many continue to cling to limiting displacement as a means of holding down cost. The usual result is designers finding expensive solutions to save weight. ⇑

11 Interestingly, only one more US battleship would complete a circumnavigation, the USS Missouri (BB-63) in 1986. ⇑

12 These were intended to be damage-resistant and stable for fire-control purposes. ⇑

Comments

I missed the part in the strategy post where Mahan particularly refuted sea denial as a strategy. Was it just that he argued persuasively for the benefits of sea control if you could afford it (which the US could)?

Pretty much. Sea denial powers rarely win wars against sea control powers, and since the US was in a position to become a sea control power (having no serious land enemies to soak up the defense budget) it was a thing we should do.

I think this would boil down to "France rarely won against England", which seems a rather slender foundation on which to erect a General Unified Theory of Naval War. You'd have to look at the respective economies and the way they interacted with finances to produce mobilisation capability, not to mention England's ability to find allies to threaten French heartland without moving a single ship. Are there any other examples of reasonably peer powers belonging to the two school fighting each other? Spain and the Netherlands were both sea-control powers as long as they could afford it, which roughly coincides with their existence as Great Powers that could fight England as equals - in fact, if anything, in 1588 it was England that was the sea-denial power, raiding the Spanish Main, and they won that one. Imperial Germany, again, would have liked to be a sea-control power and built a navy accordingly; U-boats were a wartime expedient. Same for Nazi Germany, which planned to have a battle fleet ready to challenge Britain in about 1945. And anyway naval warfare was hardly decisive in either of those cases except in keeping Britain in the fight.

I can't offhand think of any examples of powers other than France explicitly adopting a sea denial, guerre-de-course, commerce-raiding doctrine as their preferred strategy against a peer competitor. Of course, a lot of powers have been forced into such a strategy by the defeat or manifest weakness of their fleet, but to include those examples risks transforming the maxim into "weaker fleets rarely beat stronger ones", which is not very interesting.

That's pretty much how Mahan developed his theory.

To some extent, this is a very modern historical method. And Mahan's theory held up pretty well to later uses of sea power, despite the relatively flimsy basis. The ability to get allies was intimately tied in with sea control. Britain won because they couldn't be knocked out, and could support allies on the continent as they chose. And because control of the sea gave them the money to support their allies.

Disagree on this one. First, the Imperial German Navy was basically created by cargo-culting Mahan, not realizing that there was no way the British would let them win the competition. The Kriegsmarine was created by cargo-culting the Kaiser's navy. In both wars, the British blockade was vital to bringing Germany to its knees. No blockade, no turnip winter. And no economic victory for Britain.

It's definitely a strategy often favored by powers who can't afford sea control. But I think this is a case of "read history backwards". The idea that the main fleet is the important thing, and that commerce-raiding is not a good strategy, is very Mahanian in origin.