The battlecruiser is perhaps the most misunderstood and maligned warship in history. Conventional wisdom states that they were the result of Jackie Fisher’s bizarre belief that “speed is armor” and that they were ultimately a mistake, as evidenced by the loss of three at Jutland and Hood’s death against Bismarck. In fact, the term battlecruiser applies to at least three different types of ship, which filled critical roles in the fleets of a century ago.

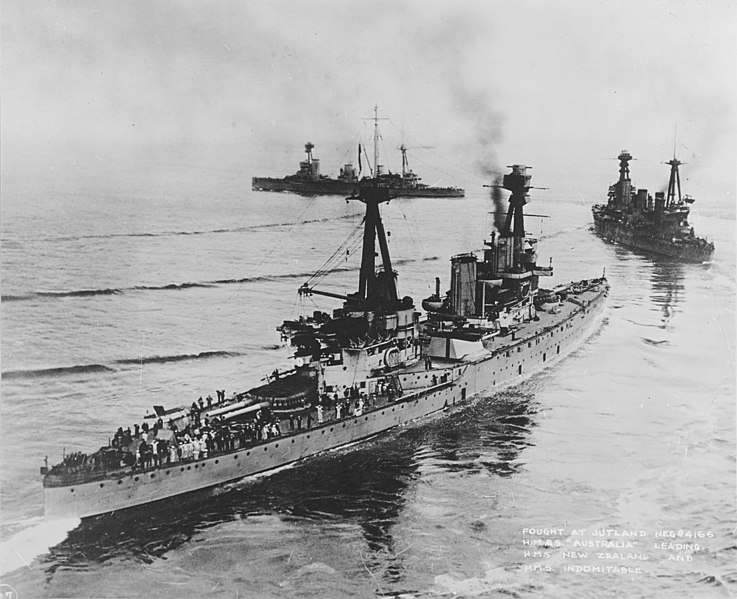

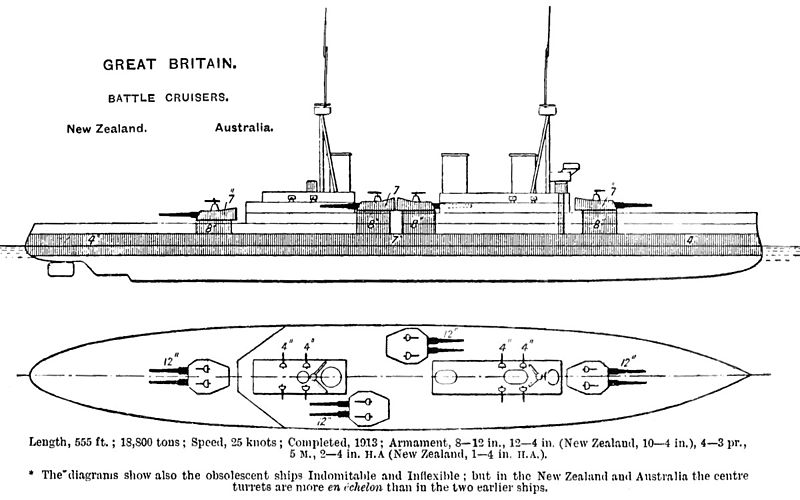

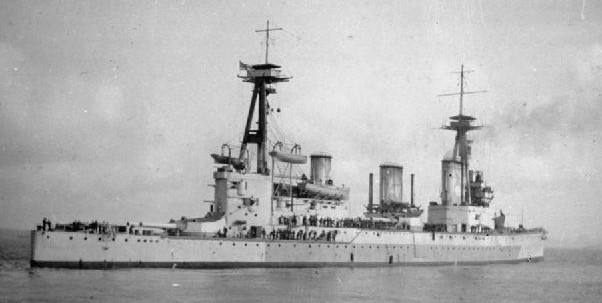

The battlecruisers Australia, New Zealand and Indomitable

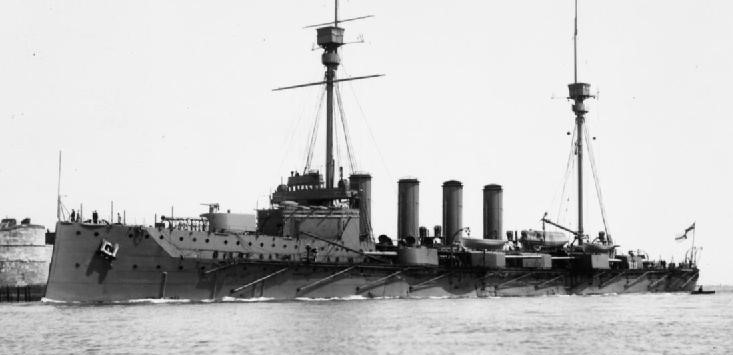

The battlecrusier has its origins in the large armored cruisers of the late 19th century. These were approximately the same size as contemporary battleships, trading guns and armor for speed and range. They were intended for trade protection, commerce raiding or working with the battlefleet, depending on doctrine. Krupp armor allowed them be armored effectively against 6″ QF guns, even occasionally matching contemporary battleships, which meant that they were often proposed as a fast wing of the battlefleet. Their armament bore this out. They had a few guns of 8″-10″, and an armament of 6″ QF guns nearly equal to that of contemporary battleships.1 The US Navy, after the Spanish-American war, built 10 large armored cruisers and gave them state names, a convention reserved by law for battleships, in recognition of their status and importance. The Royal Navy agreed, classifying those ships as battleships instead of cruisers. It was generally recognized that the armored cruiser and battleship would eventually merge into a fast capital ship.2

Armored cruiser HMS Minotaur

This posed a serious problem for the British. As the power most dependent on worldwide trade, they decided they needed a 2:1 ratio in armored cruisers over the largest other naval powers (and their likely rivals), France and Russia. But a ship as big as a battleship costs as much as a battleship, and the Boer War was a serious drain on the Exchequer. To stop the bleeding, Jackie Fisher was installed as First Sea Lord, the professional head of the Royal Navy.

Armored cruiser USS Montana

His plan to reduce the number of ships required to protect British trade had two parts. First, he would revolutionize how his forces were used. Instead of dispatching ships to search for raiders on their own, raiders would instead be tracked using information gathered from a wide variety of sources3 and analyzed centrally, and ships would then be routed to intercept via radio.

HMS Warrior

The second part was new ships, faster and more heavily armed than anything that had come before. Turbines meant that they could reach the unprecedented speed of 25 kts, and could sustain high speeds over long distances in response to radioed orders. The need for good radio performance lead to very tall topmasts being fitted. And they were fitted with an all-big-gun armament, giving them an edge in long-range firepower over anything else afloat. Some initial plans had them fitted with 9.2″ guns, but these were soon replaced with 12″ for the express purpose of giving them the capability to stand in the line of battle when necessary.4

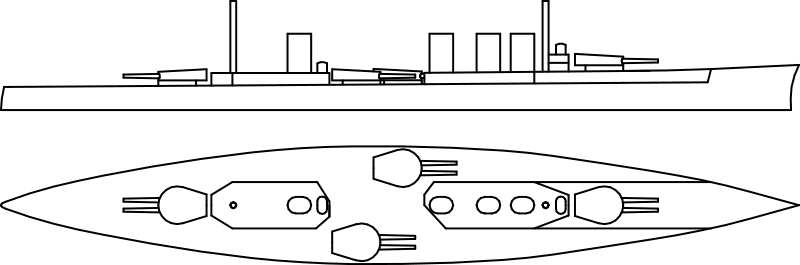

The initial design for the Invincible class

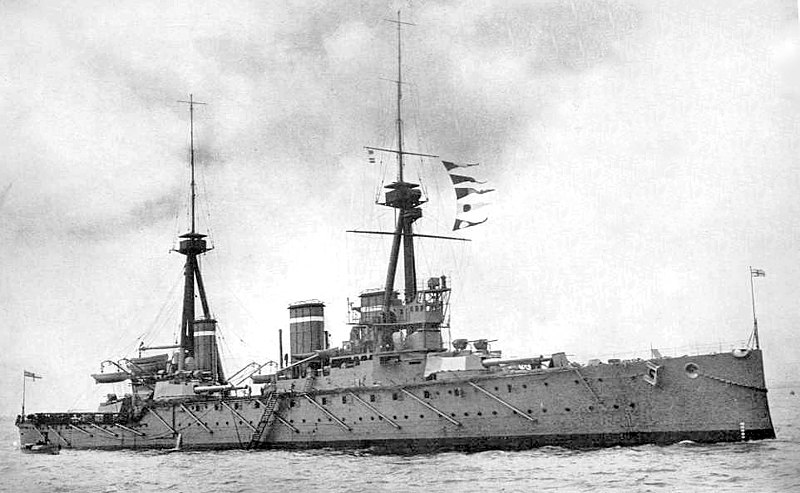

Of course, sacrifices in armor were necessary to keep the ship’s size under control, and the first battlecruisers were no more heavily armored than the last armored cruisers. It was believed that by staying at long range and using their speed to throw off the enemy’s fire control, Fisher’s dictum of “speed is armor” would actually prove true. Fisher also argued that they were unlikely to fight enemies directly on the broadside, and that the increased angle of incidence on the belt would increase its effectiveness dramatically. Oddly, neither he nor anyone else seemed to have considered what would happen when other nations began building similar ships.

HMS Invincible

As a sign of how seriously the raider threat was taken, the 1905-1906 program contained only one battleship, Dreadnought, but three battlecruisers5 of the Invincible class. This is often overlooked because Dreadnought entered service much earlier, but it shows Fisher’s real priorities.

Diagram of the Invincible class6

The resulting ships were the same displacement as Dreadnought, although the need for high speed meant that they were 40′ longer. They were armed with 4 twin 12″ turrets, one forward, one aft, and two amidships, staggered to give at least a theoretical capability to fire 4 guns ahead and an 8-gun broadside. In practice, neither capability worked very well due to blast interference, although it remained an option in battle. The 6″ armor belt was a major step down from Dreadnought’s mix of 11″ and 8″ belt armor, and the deck armor was slightly reduced, too. At the time, battle ranges were still relatively short, and recent improvements in guns and shells, particularly the development of the AP cap, had made it impossible to armor a ship against AP projectiles. Over the next decade, increasing battle ranges made armor a practical choice again, leaving the early battlecruisers very vulnerable. The Invincibles were also fitted with 4″ secondary guns, instead of the 12 pdr (3″) guns of Dreadnought, a reflection of the growing size and toughness of destroyers.

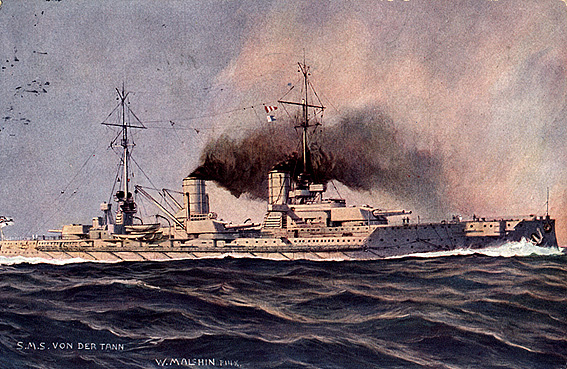

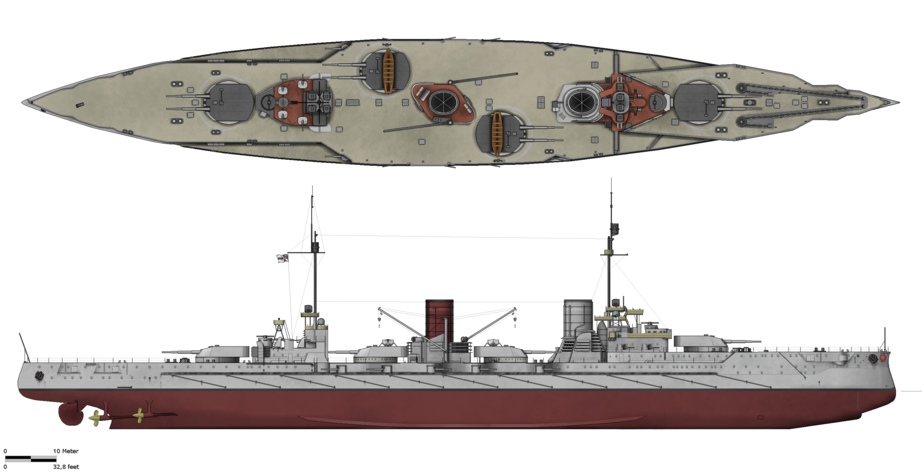

SMS Von der Tann

On the other side of the North Sea, the Germans responded by laying down battlecruisers of their own, starting in 1908.7 The first of these, SMS Von der Tann, was slightly larger than Invincible, and the result of a very different set of tradeoffs. The Germans could not afford to build enough ships to match the British, and decided to prioritize armor over guns to allow their battlecruisers to fully stand in the line of battle with the battleships. Von der Tann’s armament was laid out much like that of Invincible, but she was armed with 11″ guns instead of 12″ weapons. She also had 10 5.9″ guns, intended to be used against other battleships in a fleet battle instead of against destroyers.8 Her belt at its thickest was 9.8″, less than an inch thinner than the belt of the contemporary Nassau class battleships. She was also considerably faster than the Invincibles, making 27.8 kts on trials, although in service her performance was limited by low-quality coal.

Diagram of Von der Tann

The following figures of displacement percentage for each system type9 show the differing practices of British and German battleships and battlecruisers early in the dreadnought era:

| Ship | Hull | Armor | Machinery | Weapons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dreadnought | 34.0 | 27.9 | 11.1 | 17.3 |

| Invincible | 36.0 | 19.9 | 19.7 | 14.6 |

| Nassau | 33.6 | 35.2 | 7.3 | 14.3 |

| Von der Tann | 31.7 | 32.7 | 14.8 | 11.1 |

After the 1905-1906 program, the British built no battlecruisers under the next two programs, due largely to Fisher’s inability to communicate his vision to politicians and the public. In 1908, it was planned to order two mini-battlecruisers, essentially a reduced Invincible with 8 9.2″ guns. However, the discovery of the second German battlecruiser meant that a half-sister of the earlier ship was ordered instead. The major difference between Indefatigable and Invincible was the greater fore-and-aft separation between the two midships turrets, to give them wider arcs of fire across the ship.

HMS Indefatigable

Indefatigable was followed by two more ships, HMAS Australia and HMS New Zealand. Australia was bought as part of Fisher’s attempt to build naval forces among the Dominions10 and was owned by the Australian government. These forces, each centered around a battlecruiser, would have fulfilled the anti-raider mission around the world while the British fleet concentrated in European waters. No other Dominion bought ships, but the government of New Zealand gifted a battlecruiser to the British.

SMS Moltke

The second class of German battlecruiser was slightly more of an improvement on its predecessor than the Indefatigable was over Invincible. The extra 3,600 tons allotted was used to buy an extra 11″ twin turret, superfiring aft,11 an extra pair of 5.9″ guns, and slightly improved armor. Two ships of the Moltke class were built, the name ship and the Goeben, later famous for her part in bringing Turkey into the war.

SMS Seydlitz as she appeared at Jutland

The last of the early German battlecruisers, Seydlitz, was a minor improvement on the Moltke. Another inch of belt and a knot of speed were added, but the armament remained the same.

Both the British and German battlecruisers were fascinating ships, in many ways well ahead of their time. The British style was an ingenious response to a difficult convergence of strategic and financial problems, and only has the reputation it does due to an operational mistake. The German battlecruiser was in many ways the first fast battleship, although in many ways it was not rooted in basic strategy like its British counterpart.12

Next time I return to battlecruisers, I’ll look at the later and more heavily armed battlecruisers: British, German, and Japanese.

1 Remember that many at the time saw QF guns as the main armament of battleships, so a ship armored against them and armed with lots of them was capable of full-scale combat. ⇑

2 This did eventually come to pass, with the fast treaty battleships. ⇑

3 Britain controlled the vast majority of the world’s undersea cables and the commercial information network centered at Lloyd’s of London, giving them unparalleled knowledge of shipping. ⇑

4 After Jutland many would claim that they had never been intended for this role, but a study of the documents produced at the time of their design flatly contradicts this. ⇑

5 It’s worth noting that the term battlecruiser wasn’t officially applied to these ships until 1911. Before that, nobody was quite sure what to call them, candidates including “dreadnought cruiser” and “cruiser-battleship”. The Germans used the term Grosse Kreuzer, “Large Cruiser” for both their armored cruisers and their battlecruisers. ⇑

6 The caption says Australia and New Zealand, but the midships turrets are close together, as in Invincible. ⇑

7 SMS Blucher, a sort of hybrid between the traditional armored cruiser and the proper battlecruiser, was built under the previous year’s program. The specifics of the Invincible class arrived in Berlin a week after she was ordered. Before that, the Germans had assumed the Invincibles had 9.2″ guns, and armed Blucher to match. ⇑

8 Germany was probably the leading proponent of this at the time, although other nations made similar decisions. ⇑

9 From Battleship Design and Development by Norman Freidman. They won’t add up to 100%, as there are items which fall outside these categories. ⇑

10 The term for the semi-independent territories like Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and India. ⇑

11 It’s slightly difficult to understand why the Germans didn’t go for 8 12″ instead, as they introduced 12″ guns in their battleships at about this point. ⇑

12 In fairness, this was true of the entire German fleet. ⇑

Comments

Wait, the Lion class doesn’t count as an early BC?

(I just started reading Castles of Steel and finished the chapter on the battle of the helgoland bight, so Beatty’s squadron is of quite some interest right now.)

My dividing line was when caliber began to escalate, and Lion had 13.5″ guns. There was also a substantial jump in armor, and a change in armament layout. The Germans had a break at about the same point in time, so I split it there.

The later-model German 11-inch guns (specifically the L/45 and L/50 models) had a higher muzzle velocity than the British 12-inch Mk X guns and Mk XI guns (855 vs 823 m/s for the L/45 vs Mk X, and 880 vs 861 for the L/50 vs Mk XI and Mk XII), which German naval planners considered to make up for the smaller shells. This may have been compounded by Germans comparing their latest guns to the previous generation of British guns, since German shipyards took considerably longer to build battleships than the British did.

I suspect a large investment in tooling for manufacturing 11-inch guns was a factor as well, since those were used in several generations of German BBs and BCs, and the German Army also used the same caliber for several railway gun models.

Note, though, that the Germans went for 12″ on their battleships at about the point Moltke was built. I think some of it was Tirpitz trying to hold down the size of his ships because of the way his budgeting was structured (long story, and one I will tell eventually), but there’s some of it I haven’t put in the time or effort to understand.

Yes, the German guns were better than their British counterparts (and I’ve actually just finished writing about this in the context of main guns) but there were other things going on. For instance, the Germans never had an intermediate gun between 12″ and 15″, and they went to 15″ before they found out about the British decision to do so.

On the other hand, the German battlecruisers were almost always an inch or so down on their contemporary battleships in terms of guns. They went for 15″ on the Bayern class, and 14″ on the Mackensen class. This is not a decision I would have made (logistical reasons, if nothing else), but it does sort of fit with traditional German defense procurement. See most of WWII.

I’m sure Tirpitz was constrained in his designs by the German Naval Laws, but another part of the decision to stick with smaller guns was the Kiel Canal. There was a project underway to enlarge the canal to accommodate dreadnought-type battleships, which completed in 1914, but that project was based on the footprint of early dreadnought designs. The larger ships designed around 15″ guns were too big for the enlarged canal, and Tirpitz was reluctant to bite the bullet and accept building bigger ships that would require a second canal-enlarging project in order to be able to pass between the Baltic and the North Sea without passing through Danish or Swedish water.

I checked Fighting the Great War at Sea, and Friedman attributes most of it to Tirpitz being trapped by the Navy Laws, which specified both ship numbers and ship cost. He couldn’t simply say “we’ll order three instead of four ships, and make each ship bigger”, because they’d be written for pre-dreads. This resulted in lots of budgetary games, and things like heavily cutting the training ammo budget. The Kiel Canal isn’t mentioned except in connection with the Nassaus. But I’m not an expert in the German navy.

I’ve noticed a lot of people tend to obsess over (a) gun caliber and (b) armor, whether the concept is tanks or battleships, but it seems to me that sensors/fire control (and the training to make proper use of it) is a huge issue that gets very little love, mostly because it’s complicated to properly understand. But fire control makes for big differences (e.g., Renown vs. Scharnhorst/Gneisanu off Norway where the German BCs’ shooting just got worse and worse during the fight).

Ammo design, too -- the British probably would have won Jutland in a big way if their shells had actually exploded upon hitting at the rate they were supposed to. Shells are actually complicated and powerful mechanisms for making things go boom, and there are lots and lots of ways for them to not work (admittedly a 16″ AP shell can still wreck your day because it punches a hole a foot and a half wide through your ship even if it doesn’t explode), but dud percentages are high enough to be noticeable even in WW II (e.g., the 15″ shell from Bismarck that found its way into Prince of Wales’ bottom spaces; had it exploded near the magazines, well, ouch).

@Tony

I’m certainly not unaware of those issues, and there’s a reason that Naval Gazing started with a discussion of fire control, and that I harp on it at every opportunity. My favorite thing to do on the Iowa was to ambush guests and talk about fire control. It’s a topic I do intend to get back to, but not until I’ve gotten the other basic technical topics updated. I’m working on main guns now, which more or less finishes the major topics, so expect that in the next couple months.

WRT this specific instance, for a variety of reasons, big guns are better than small ones, and I do think that I’d have looked very very hard at going to 8x12″ over 10x11″. I don’t have the precise numbers to know what would have happened, but at the very least, it means you’re using the same guns and ammo as the battleships.

I thought this was as good a place as any to point out another accomplishment of Jacky Fisher: he (may have) coined the term “OMG”. http://newsfeed.time.com/2012/11/29/omg-first-use-of-abbreviation-found-in-a-letter-to-winston-churchill/

@Andrew

I’m somehow completely unsurprised by this. I still can’t quite make up my mind of Fisher. He was clearly a genius, but also unstable. For every very good idea, he also had a bad one. One of these days, I’m going to write a post on him, so I can link to it instead of wiki.